New book shares stories of South Side women, uncovers broader picture of social injustices

February is Black History Month — a time set aside to remember the significant contributions by people of the African Diaspora to America and the world. Yet, there are those who argue that black people have had little or no positive impact.

As I reflect on our many contributions, I recall an old African proverb: “Until the lions become the historians, the hunters will always be the heroes.”

The lesson: a people that have no voice will always be depicted as the losers. We must find our own voices, capture our own visions and tell our own stories.

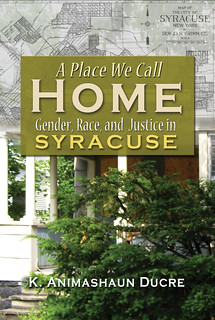

In her book, “A Place We Call Home: Gender, Race, and Justice in Syracuse,” K. Animashaun Ducre shares the stories of 14 black women as they struggle to survive in an impoverished neighborhood on the South Side of Syracuse. Using Photovoice methodology and community mapping, she captures their voices, visions and stories. Ducre chronicles the role of race, gender, environmental justice and space in the city of Syracuse. In doing so, she uncovers a bigger story about “the policies of social institutions … that prohibit the physical and social mobility of the poor and communities of color …” denying black and poorer residents “access to affordable, safe and clean housing” for 70 years.

In her book, “A Place We Call Home: Gender, Race, and Justice in Syracuse,” K. Animashaun Ducre shares the stories of 14 black women as they struggle to survive in an impoverished neighborhood on the South Side of Syracuse. Using Photovoice methodology and community mapping, she captures their voices, visions and stories. Ducre chronicles the role of race, gender, environmental justice and space in the city of Syracuse. In doing so, she uncovers a bigger story about “the policies of social institutions … that prohibit the physical and social mobility of the poor and communities of color …” denying black and poorer residents “access to affordable, safe and clean housing” for 70 years.

“A Place We Call Home” is the first book-length presentation using the Photovoice process — a concept developed by Caroline Wang at the University of Michigan in the early ’90s.

“Photovoice is basically giving cameras to folks who have been underrepresented in their community’s planning process to understand what they think and value,” Ducre said. “The photographers meet periodically to present their images to one another as a means to discuss their community [or] issue.”

At the end of the process, an exhibition is held and the selected images are presented to the larger community for debate and discussion.

Volunteers from a local community health center helped Ducre recruit the women for the Photovoice project. Ducre  randomly selected 14 women from an initial list of 34. Each participant received a digital camera, memory card, rechargeable batteries, camera bag and $40 per Saturday for participating.

randomly selected 14 women from an initial list of 34. Each participant received a digital camera, memory card, rechargeable batteries, camera bag and $40 per Saturday for participating.

Ducre assigned each woman pseudonyms to protect their identity. She gave them the names of black female icons to honor them. For example, she named one of the women after artist Faith Ringgold.

“Like the artist, Faith’s deep creativity came out in her photography,” Ducre writes. Her work was so creative that Syracuse University Chancellor Nancy Cantor featured one of Faith’s photos in a public address.

One of Faith’s photos featured in the book is titled “First Thing I See.” It shows an abandoned house that is located across from her home.

“It’s been like this for years. I just wonder when they’re going to fix it up … it’s right here every day when I come outside — it’s the first thing I see,” she writes. “I just call it the Homeless House ’cause it’s a house that nobody fixes up.”

Abandoned and deteriorating houses are nothing new to the South Side. Through community mapping and Photovoice, Ducre uncovers a story about the designation of a particular area “for racial and ethnic minorities as a means of containment and social control.”

“As a sociology scholar, I think my role is … to link historic injustices to contemporary social problems related to inequality. As an activist, I feel it is my duty to confront injustice and challenge inequality. I am motivated by a sense of fairness and equity.”

Initially, the women saw Ducre as an outsider. She identified with them, but they saw her as a professor from the SU hill. She felt uncomfortable revealing so much about them without revealing herself. “I felt that I had to be down with them in sharing my story,” she said.

Through their stories, she discovered her own.

“As far as the social aspects, I grew up in neighborhoods very similar to the demographics of the South Side,” she shared.

Her mother, grandmother and great-grandmother raised her in predominantly black and low-income neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., and Maryland.

She recalls the time the family was evicted and their “belongings being tossed out and littering the entrance of the complex,” she writes. “I recall feeling complete devastation, looking at my mother’s black-and-white couch and other pieces of our lives sitting on the curb.”

— By Keith Muhammad, Community correspondent for The Stand

The Stand

The Stand