VIP Structures, others celebrate its report on hiring of minority and lower-income workers

The community had its eyes on the Price Rite project as it finally came together last year. And on the people who built it.

What did they see?

A job site like no other, says Russell Mike, whose construction company got some of the work as a subcontractor on the new supermarket. It’s a project, he and others believe, that could be a template for the future to assure more people of color, and more of the city’s lower-income residents, get a larger share of the work on big contracts.

Mike, an African-American and owner of Ram Construction, says that people actually could see the results of a voluntary collaboration on Price Rite that resulted in unprecedented hiring of minorities, many of them from the low-income neighborhood. The job site at 611 South Ave. felt different, and it was.

“The need is tremendous,” Mike said in an interview last month after a report was completed that detailed hiring data on the Price Rite job for minorities and for the city’s lowest-income residents in 11 targeted ZIP codes. “Just watching my presence alone,” Mike said, “a lot of bystanders walking by seeing me or seeing a couple other guys working there and for them knowing what was being built, what was coming up, and knowing that there were going to be opportunities for them also, it was good seeing all of that energy.”

A report by VIP Structures, general contractor for the work, showed the firm aimed to hire 25 to 30 percent minority and lower-income workers who were “boots on the ground” actually working on the site. That’s a much bigger commitment than government regulations that require such a percentage of minority and women-owned contractors, or bosses, not the people they employ.

The report, titled “A Case Study of the Initiative to Increase Local Hire and Minority Participation in Construction of the South Ave. Syracuse Price Rite,” was finished in December 2017 and hasn’t been widely circulated, but it’s being celebrated across the ranks — by the contractors, business and government groups, advocates for minorities and the lower-income, and by workers themselves who reaped the benefits from a unique hiring model.

The final tally: 29.2 percent of all workers were minorities and 28.8 percent were drawn from the low-income ZIP codes. (Two of every three workers from the targeted ranks fit both criteria: a minority who also was from one of the ZIPs.)

The final tally: 29.2 percent of all workers were minorities and 28.8 percent were drawn from the low-income ZIP codes. (Two of every three workers from the targeted ranks fit both criteria: a minority who also was from one of the ZIPs.)

David Nutting, CEO of VIP Structures, says work funded by government money, in part or in full, requires developers to hire a percentage of the contractors who are women and minorities. For the Price Rite project, the state-funded portion totaled $600,000 and VIP Structures was required to meet a 30 percent hiring goal for what is called M/WBE contractors (minority and women).

“Where it really falls short from my point of view is I don’t really want to hire a contractor, I want to hire people who are actually working, and regulations don’t deal with that at all,” Nutting said. “You can be a woman-owned business and hire nothing but white males. You can be a minority-owned business and hire nothing but white males.”

Nutting explained that approximately $180,000 had to be spent on M/WBE contractors, which would be 4.5 percent of the total $4.1 million budget. With the state-funded portion of the project being much lower than the total cost of it, the M/WBE goal had already been met in the architecture planning alone.

The voluntary goal that he agreed on with community advocates went far beyond and was endorsed by groups that can at times be at odds with businesses that must protect profits.

“The project was the opportunity to support and invest in a part of our city that has not seen investment for the better part of two or three decades,” said Rob Simpson, president and CEO of CenterState CEO.

Simpson had been talking with Walt Dixie, executive director of Jubilee Homes, for over a decade about the need for a grocery store on the South Side. The area has been tagged as a “food desert,” where residents do not have adequate access to cheap and healthy food.

“It was really wonderful to be able to work with folks like Jubilee Homes, and neighborhood stakeholders, to work with our economic development officials here at the state and locally, as well as a major national company like Price Rite, to bring an investment, to bring a grocery store and to bring much-needed jobs to a neighborhood that, frankly, desperately needed them,” Simpson said.

The store, which opened April 2, 2017, employs around 75 now. (The government-subsidized project has not been without some negatives, primarily the closing of the nearly 100-year-old, privately owned Nojaim Brothers supermarket on the West Side, whose demise some have blamed, at least in part, on the Price Rite venture.)

That debate aside, local leaders had been looking for a project — no matter what the extent of government funding — where sometimes-competing interests could coalesce around a deeper hiring commitment to minority and lower-income workers down to the most elementary jobs and skill levels, not just M/WBE contractors. Those interests included Simpson, Reggie Seigler, who is Section 3 coordinator at the Syracuse Housing Authority, and Aggie Lane, who at the time was president of the Urban Jobs Task Force. They met regularly, focusing on finding a test case project that could be voluntary.

“First and foremost, it was about finding a partner that was open-minded and willing to try new things, willing to have a difficult conversation about race and employment,” Simpson said. “That’s not always an easy thing to do. It was a combination of those things that led us naturally to VIP Structures. They were very open to the dialogue, enthusiastic about the project, and they were a phenomenal partner.”

“First and foremost, it was about finding a partner that was open-minded and willing to try new things, willing to have a difficult conversation about race and employment,” Simpson said. “That’s not always an easy thing to do. It was a combination of those things that led us naturally to VIP Structures. They were very open to the dialogue, enthusiastic about the project, and they were a phenomenal partner.”

The group met with Nutting — who is white — to discuss how to create a more inclusive work site with bigger goals.

“The only way to make it happen is to do it with people who want to do it, and that’s the way we were able to make this happen,” Seigler said in an interview in his SHA office. “We did it in a way to create a model to show other developers. We need a guy like Dave Nutting who can say, ‘OK, we can do this, I did it, and I’ll do it again,’ and we can make this model happen without compromising our bottom line, without having to pay more for services, while at the same time getting a workforce trained that we can look at and use.”

According to the Census, in 2016 the poverty rate for Syracuse was the 13th highest of approximately 65,000 cities across the United States, deteriorating drastically from being ranked 29th nationwide the year before. The average household income for the city of Syracuse was recorded at $33,695 in 2016 for a family of four. The unemployment rate among blacks: 16 percent compared with 6 percent for the city overall.

Nutting said he depended heavily on Seigler and Lane, and they came through, soliciting “anybody they could find to help.”

His message: “We have the jobs, we have the willingness, we want to make this happen but we really need help finding qualified minorities to work on the projects.”

Nutting and his wife moved to Syracuse in 1975, and he said they felt supported when he started his business.

“We really had people go out of their way to invite us into the community, so we owe a lot to the city,” Nutting said. “A significant portion of who we are is trying to figure out how to give back.”

Instead of sending out a formal letter and requiring his subcontractors to sign an agreement, Nutting made it voluntary, hoping to persuade them to intentionally hire local minority workers. Most subcontractors have crews that not only can get the work done at lowest cost but who are also reliable and trusted.

“The harder it is to actually do something in Syracuse, the worse it is for Syracuse, so if it can be done voluntarily, if it can become part of the norm, and if through doing it more and more there can be more people available for job sites, that’s going to be better for everybody,” Nutting said.

VIP Structures monitored and checked the hiring and site reports regularly to see if the goal of hiring minority workers, especially from impoverished ZIP codes, was 25 percent of the workers on the site or higher. Nutting acknowledged that he did not push the contractors as much as he might have.

Most of the subcontractors were willing to commit to the minimum requirements set out for hiring workers.

“Some were great. Some were not,” Nutting said. “They were human beings but most of them were pretty darn good. We do a ton of work so we have some clout, but it’s disappointing to get to the end of the project and not have anybody on the site crew hired from the neighborhood or a minority.”

Construction began around July 6, 2016, and all workers were off site by the end of May 2017. Although the store opened in April, there were a few workers on site to perform “punch list” items, the final detail work.

At the start of the project, the number of minorities from the target ZIP codes went as high as 50 percent but as the project progressed, those numbers dwindled as the work became more technical, requiring more skills.

“We’d probably, in doing it next time, would be saying, ‘Come on, you got to do better,’ and push it along a little better,” Nutting said.

Lane is now vice president of the Urban Jobs Task Force (UJTF), which is a coalition of organizations and residents of the city of Syracuse and Onondaga County. The task force advocates for training and job opportunities for the unemployed, especially from communities of color and low-income families.

On this project, Lane said she realized how much dedication it would take to change the situation. She mentioned that people who already are getting work, such as those in the building trades, are already connected.

“Someone’s family may have been in that trade, a child may have grown up with a father in the building trades, he has taught the trade, or his father was in the union,” Lane said. “There are those that are very connected to that and then those who aren’t.” People of color, she said, “because of racism and segregation in our country,” don’t get opportunities. “How do you combat that?”

Lane said she believes one way is to find and recruit people like Nutting.

“There aren’t many David Nuttings in the world that put that much time in it,” Lane said. “I believe in goals because I don’t think people will just do them since it’s hard work.”

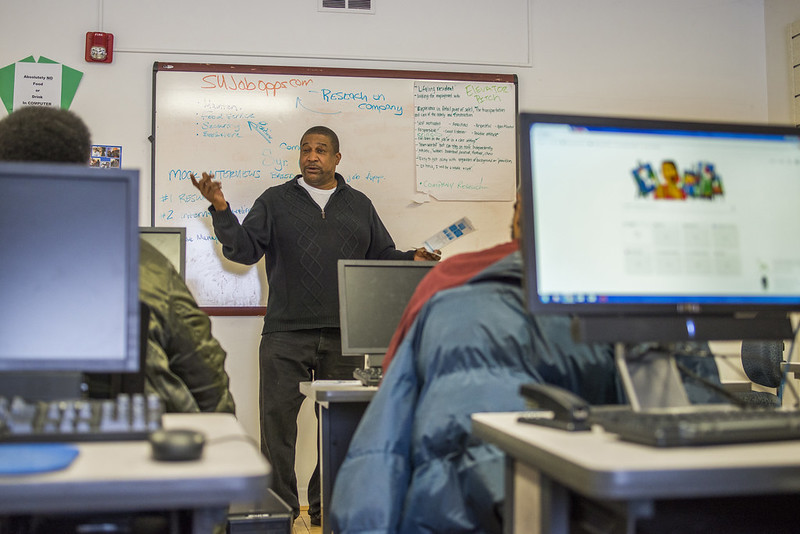

At the beginning of the project, Syracuse Housing Authority, Jubilee Homes, Tradesmen International, and VIP Structures hosted a job fair at the Syracuse Chamber of Commerce. Seigler did recruiting, including everyone who could be involved to help the hiring go more smoothly, as well as the people who participated.

Seigler helps his tenants and low-income residents find employment and opportunities. He reached out to Twiggy Billue from Jubilee Homes and to others throughout the city and county to identify workers from impoverished ZIP codes.

Nutting said that was vital.

“It was everything,” he said. “I don’t have access to the neighborhood. We may eventually over time, but we really have to rely on folks who have access. Certainly, Reggie has a job which brings him into contact with an awful lot of contractors and people who work in the trades, so he was enormously helpful. Then he really expanded. He went to a number of other folks to help out as well so he was probably the most key to this.”

Urban Jobs Task Force works with Jubilee Homes, which has a workforce development program called Build To Work, and it brought its participants to the job fair. Rickey Brown of Upstate Minority Economic Alliance was involved, helping find minority contractors to meet the Minority Business Enterprise Goal. He is bilingual and assisted Spanish-speaking residents who were present.

“About 60 people showed up to be interviewed by Tradesmen International for them to find the best candidates, catalog their skills, and put them in their database, then these contractors could hire them through Tradesmen,” Lane said.

“About 60 people showed up to be interviewed by Tradesmen International for them to find the best candidates, catalog their skills, and put them in their database, then these contractors could hire them through Tradesmen,” Lane said.

Tradesmen International also assisted workers with the process of obtaining required licenses and certifications.

For almost 20 years, Russell Mike has worked with VIP Structures, as part of his Ram Construction business, or as an independent worker when opportunities were available. He was encouraged to see so many young people from his neighborhood attend the job fair.

“A lot of these younger guys, with my color, my culture, they don’t understand how to go about working,” Mike said. “They don’t understand some of the language. They take a little more patience.”

The Price Rite team continues to meet.

“The lesson for me, and it wasn’t really surprising but it was really gratifying, is that when stakeholders sit down at the beginning of a project and identify their goals and their needs, that collaborative solutions are easy to find,” Simpson said. “I think all too often, whether it’s in economic development, politics, or whatever realm, we end up in situations where people don’t really want to talk with each other and understand where they’re coming from. They’d rather argue about things incessantly. For me, the reinforcing lesson here is that really good, honest, transparent dialogue on the front end saves a lot of time on the back end. And frankly, it leads to better outcomes in the community.”

One of the contractors on the project was NaDonte Jones, who started N.J. Jones Plumbing LLC. He is the only black master plumber in Syracuse and is a Section 3 contractor. Section 3 ensures that preference for training, employment and contract opportunities provided by certain funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development be given to local, low-income residents — specifically those who receive federal housing assistance and businesses that employ or are owned by them. Jones saw the need for training workers and started an apprenticeship program.

“I started the first and only minority-directed plumber apprentice program,” Jones said. “We got it approved by the New York State Department of Labor in 2016.”

Jones had a total of four employees on the Price Rite project, and he was on the job approximately 25 to 30 percent of the time. One employee was a journeyman plumber who has a minimum of five years experience in the field, and three were apprentice plumbers, all of whom were minority. One additional employee was white and was on the job for two to three weeks.

“Definitely from a standpoint of it not being mandated by the state or the owner of the property, or whoever is funding the project, that was one of the most diverse worksites I’ve been on with it not being a requirement,” Jones said.

Each person involved in the planning and development of this project has looked ahead at how they can continue to work together and find other developers and community members to try this approach.

Nutting said he has worked with Seigler recently on The Post-Standard building downtown, which VIP Structures is redeveloping for its own office as well as for two or three new floors of residential units.

“We needed a couple of unskilled people starting out because we’re taking down ceilings and some other stuff so Reggie found us two people who are Section 3 housing, who are great workers. Reggie is helping us source things as we come along.”

Nutting said he understands workers need to get to the job site, but he recently asked his human resources department why workers are required to have a driver’s license. Just getting to work is all that matters, he said. He wants Seigler and Brown to look through VIP Structures’ employee manual to see if other such requirements are getting in the way of work for people from the South Side and other neighborhoods.

“If we’re going to do this right, we’re going to have to go to transportation,” Nutting said. “How do we get people to job sites? We’re going to have to eventually go to the elementary schools to get kids excited about construction jobs and architecture jobs. We’re kind of picking up at the back end when people may not have skills, and we really need to push it down to the aspirational level.”

Nutting said the Price Rite collaborative will need to stay together to bring in more developers.

“The good news about (Interstate) 81 is they have the ability from a governmental point of view to have requirements,” Nutting said, looking ahead to the highway rebuilding project that will cost $1.5 billion or more. “I think (Mayor) Ben Walsh and we’re all trying to get ahead of 81, and it’s coming down the pike. How do we make sure there are some qualified minority workers that can work on the I-81 project? What would that be, what would that look like? What skill sets do they need? People like Reggie will be in great demand because he knows a ton of subcontractors who are out there now that will be able to do some of the work. Can they break the work into small enough pieces that enough people can work on it?”

After working on the Price Rite project, Mike continues to envision a mentorship program that he has thought about for years. It would connect workers who could use more skills and training and contractors who lack the resources with developers like VIP Structures who have the experience and opportunities.

“For a lot of us, it’s a struggle,” Mike said. “We get one job, then we may not get another job for another six months. By that time, you’re almost out of business.”

He was inspired by how VIP Structures reached out to the community, working with others not only to help build a project while mentoring workers, but also to share a model that could encourage more mentorship from other developers.

“It takes a different avenue to reach some of these guys, to bring them out, to want to work, and to let them know the nature of them building up their community, our community,” Mike said. “It just takes someone from the community to try to give them that guidance and show them that this can be done.”

— Article by Julianna Whiteway, Urban Affairs reporter

The Stand

The Stand