Save the Rain planting program prevents pollution

The South Side has gotten a little greener as a local environmental organization has planted about 700 trees throughout the neighborhood.

Over the past two months, The Onondaga Earth Corps planted the trees to absorb and prevent storm water from carrying pollution into local bodies of water, said Keenan Lewis, the group’s youth program coordinator.

The Earth Corps is a small branch of the Save the Rain initiative, a public program whose mission is to find creative solutions to prevent any further pollution of Onondaga Lake, which used to be recognized as one of the most polluted in the entire U.S.

But Lewis said he hopes to accomplish more than just a clean neighborhood. He said it is also an opportunity to educate young community members to build an environmentally conscious foundation for them to use in the future.

“If we give kids knowledge to understand the environment, it accomplishes two things: One, it puts the city in good hands. Two, it keeps kids off the street,” Lewis said.

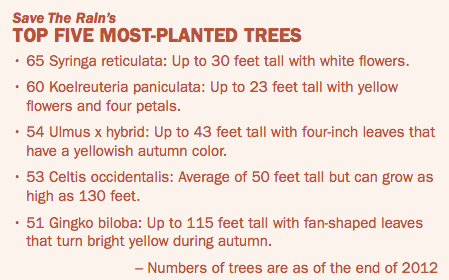

The trees on the South Side are part of the Save the Rain Tree Planting Program, which is a collaborative effort between neighborhoods to plant 8,500 trees by 2018. The South Side’s new trees constitute about 1 percent of the goal.

Save the Rain came to fruition after Onondaga County was sued under the Clean Water Act. Consequently, in 1989 the county agreed to cease dumping into Onondaga Lake, and in 1998, the county worked out a plan to contain sewage overflows into the lake.

While the program is the result of an amended consent judgment and is administered by Onondaga County, other programs like the Onondaga Environmental Institute help grow these programs. The institute is an organization that advances environmental research and restoration in Central New York, and works to prevent combined sewage overflows, which threaten the city when it rains, said Molly Farrell, a staff member at the institute.

Syracuse has a combined sewer system, meaning wastewater from homes and businesses, and storm water from street drains flow through a single pipe system to a water pollution control plant. In the event of heavy rain, the water flow exceeds the capacity of the pipes and overflows into nearby streams, rivers and lakes.

The polluted water — also known as greywater — has harmful effects on the environment, Farrell said.

The polluted water — also known as greywater — has harmful effects on the environment, Farrell said.

To impose a more affordable solution than replacing the sewer system, the institute collaborated with local organizations like the Environmental Finance Center, which provides asset management and budgeting tools for achieving sustainability, and the Southside Interfaith Community Development Corporation, which works to create a higher quality of life for residents in the South Side. This resulted in green infrastructure, which has been gradually integrated into residential areas.

“Cities are a problem because in them you find brick, concrete, trash and other pollutants,” said Amy Samuels, education and outreach coordinator of the Onondaga Environmental Institute. “On top of that, houses have their own construction debris and waste.”

The most effective way to decrease overflow, Farrell said, is to absorb the excess water before it has the chance to merge with the sewage contents. To do that, water-absorbing infrastructure needs to be planted at the source. And the sources in this case are residences where water runoff accumulates quickly.

“The more industrial a place is, or lived on, the more waste there is going to be,” Farrell said.

The solutions that environmental organizations have been implementing are things like planting trees, rain gardens — dug out areas inhabited by na- tive plants that absorb water from impermeable sources — and roof gardens, which act as a way to slow rain runoff from roofs. In addition, there are rain barrels and porous pavement, all systems to prevent the runoff from picking up speed and eroding property, flooding and carrying pollutants to lakes.

The Onondaga Environmental Institute is currently planting these water-absorbent and eco-friendly infrastructures in residential areas, often in the backyards of houses owned by people willing to let the staff give tours on the property.

Wider-sweeping measures are also being implemented to expand the institute’s reach. Samuels said there are more “green-street makeovers” happening in Syracuse’s neighborhoods. The makeover’s goal is to fill the entire length of certain streets with green infrastructure that will collect, divert and even reuse storm water.

The Stand

The Stand