Janks Morton’s documentary “Hoodwinked” starts out with a bang: black and white footage showing a fiery speech from Nation of Islam minister Malcolm X in which he responds to accusations that Elijah Muhammad, the Nation of Islam leader, was promoting hate.

Janks Morton’s documentary “Hoodwinked” starts out with a bang: black and white footage showing a fiery speech from Nation of Islam minister Malcolm X in which he responds to accusations that Elijah Muhammad, the Nation of Islam leader, was promoting hate.

The flick was part of a free double feature screening that took place at the corner of South Salina and East Colvin streets July 18 with about 40 neighbors in attendance. It was preceded by “Syracuse’s 15th Ward and Beyond.” Both documentaries were sponsored by a partnership that included the South Side Initiative and the Southside Community Coalition. The next screening is Thursday, July 25, of “Brave.”

Setting the tone for the rest of the film, the following quotation advocates for “soul-utions”: “Who taught you to hate yourself from the top of your head to the soles of your feet? Who taught you to hate your own kind? Who taught you to hate the race that you belong to so much so that you don’t want to be around each other? You know. Before you come asking Mr. Muhammad does he teach hate, you should ask yourself who taught you to hate being what God made you,” Malcolm X says in his speech, delivered on May 22, 1962. “Teaching a man to hate himself is much more criminal than teaching him to hate someone else.”

This quotation identifies instances of “self-hate” in the African-American community.

“You need to dig deep, find who you are and who you want to be, love and embrace,” Morton posits as one of his “solutions.”

“Hoodwinked” seeks to “emphasize the positive instead of the negative,” Morton says, listing a litany of negative stereotypes commonly attached to black males: “incarcerated, uneducated, down-low, white-woman-chasing, unavailable, thug, mandingo, mystical, unemployed, diseased, materialistic.”

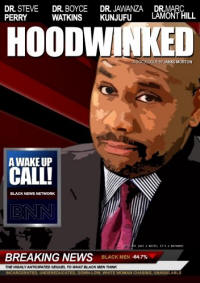

To participate in his “doculogue” (documentary designed to create dialogue), as he calls it, Morton assembled a team of talking heads, all of whom are black intellectuals working in the educational field as principals, professors or consultants. The star-studded lineup of brain power is made up of Dr. Boyce Watkins, Dr. Steve Perry, Dr. Marc Lamont Hill, Dr. Ivory Toldson and Dr. Jawanza Kunjufu.

The pundits’ role is to debate the core of the film, which consists of clips from a lecture given by Morton “obliterating” with statistics 11 “typecasts” about black males and females: “black men are more engaged in crime than education, black males are falling behind in education, black men are uneducated menaces to society, black women are more suited to be the help than educated, black boys are the special needs burden of education, there is a shortage of educated black men on any level, black males are wired for failure not higher education, black females desire to be housewives, black men are uneducateable and ignorant,” etc.

Watkins, a scholar in residence in entrepreneurship and innovation at Syracuse University, and Kunjufu, an author of 29 books, seem particularly qualified to analyze the issue of black children being disproportionally segregated in special education.

Watkins, a scholar in residence in entrepreneurship and innovation at Syracuse University, and Kunjufu, an author of 29 books, seem particularly qualified to analyze the issue of black children being disproportionally segregated in special education.

“I was not, according to my teachers, cut out for college and my teachers even recommended me for special education and medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).” Watkins says. “What I didn’t know at the time is that black boys are 5 times more likely to be placed in special education than kids of other ethnicities.” In spite of this misdiagnosis, Watkins went on to earn a doctorate in finance from Ohio State University.

For his part, Kunjufu, in his book “Keeping Black Boys Out of Special Education,” writes: “Many African-American males are erroneously placed in special education, when in reality they possess the following gifted and talented characteristics: keen power of observation, sense of the significant, willingness to examine the unusual, questioning attitude, intellectual curiosity, inquisitive mind, creativeness and inventiveness, high energy levels, need for freedom of movement and action, versatility, diversity of interests and abilities, and varied hobbies.”

For the sake of brevity, instead of describing one by one all the points raised by the filmmaker, it would make more sense to limit the scope to a representative sampling of them.

First of all, Morton examines the popular belief that there are more black men in jail than in college. He cites the latest U.S. government statistical data available when he made his documentary. The tables that he shows indicate that there were 824,340 black men in jails (including military jails), federal and state prisons, private correction facilities, juvenile detention centers and institutions for the criminally insane combined whereas 1,444,979 black men were matriculated in college. He says that the opposite opinion stems from taking data for incarcerated black men for a whole year and comparing it to data for the fall semester only for college enrollment.

A second contention that Morton evaluates is: “It’s common knowledge that 50 percent of black boys drop out of high school.” The film director says that this figure is inflated because it considers only students who graduate with their cohort, meaning that those who transferred to another school or repeated the grade aren’t included in the graduation with their cohort rate.

Between 2000 and 2010, young black males have made significant progress, Morton’s sources suggest. In this period, their high school graduation rate went up, from 76.6 percent to 81.7 percent, while their dropout rate decreased from 15.3 percent to 9.5 percent. In addition, their college enrollment rate climbed from 5.2 percent to 6.9 percent at the same time that the incarceration rate (for ages 18-24) declined from 8.3 percent to 6.2 percent.

These data question the extent of the validity of conventional claims, mentioned in the film, in regard to black boys such as “public schools are dropout factories, there is a cradle to prison pipeline and information on grades in the third grade are used by the U.S. government to build prisons.”

Despite the progress argued in the film, not everything is fine and dandy in the African-American community. Schools districts in cities such as Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington are failing blacks, Kunjufu says. “Parents with children in failed schools should sue the schools for damages,” adds Perry, founder and principal of Capital Preparatory Magnet School in Hartford, Conn., and CNN education contributor.

In order to achieve a positive stereotype, the black community should stop listening to the media because they are telling a story to sell and they whitewash the minds of blacks to make them internalize white supremacy, Hill says. Watkins weighs in by saying that “life imitates art and art imitates life as well” and messages in the media become “self-fulfilling prophesies.” Finally, Perry recommends not to “buy into the crisis industry.”

An example of alleged media sensationalization presented in the film is that of television and radio personality Steve Harvey having told his audience that 42 percent of African-American women aren’t married without mentioning

that 45 percent of all American women aren’t married, according to statistics compiled by Morton.

The issues described in “Hoodwinked” could be better understood by reading its companion book “Black People Don’t Read: The Definitive Guide to Dismantling Stereotypes and Negative Statistical Claims about Black Americans” by Morton and Toldson, editor-in-chief of The Journal of Negro Education, and foreword by Kunjufu.

In the book, the authors elaborate on the reasons for the persistence of “imageries, myths, falsehoods, narratives,

misinformation and negative lenses” in the African-American community, in an effort reminiscent of Peter Reuter’s article “The (continued) vitality of mythical numbers,” published in National Affairs in 1984.

The basis for Morton and Toldson’s analysis comes from a psychiatrist, Frantz Fanon, who, in his book “Black Skin, White Masks” writes: “Sometimes people hold a core belief that is very strong. When they are present with evidence that works against that belief, the new evidence cannot be accepted. It would create a feeling that is extremely uncomfortable, called cognitive dissonance. And because it is so important to protect the core belief, they will rationalize, ignore and even deny anything that doesn’t fit in with the core belief.”

But humorist Mark Twain, without having a psychiatry degree, says it better, “Never let the facts get in the way of a good story.”

– Review by Miguel Balbuena, Community Correspondent for The Stand

The Stand

The Stand