One man takes his mission to end violence in his neighborhood to the corner of West Colvin

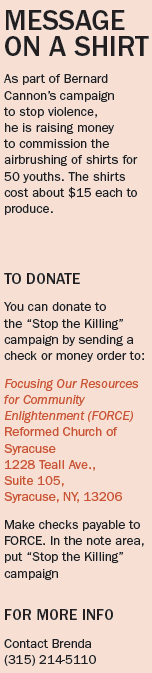

Bernard Cannon is no stranger to violence. His mother was shot and murdered in front of him when he was 10 years old. In the 30 years since her death, he has witnessed many families torn apart by senseless violence. Watching adults peek out of their windows afraid to get involved, and refusing to be a prisoner to the violence in his community, he decided to do something about it. Cannon began a one-man crusade to encourage residents to come out of their houses to stem the tide of violence plaguing the community. He came up with an idea for two banners to bring awareness to the issue. He hopes to raise money that will commission the airbrushing of shirts for 50 youths as part of the campaign.

You will find Cannon and his banner in a parking lot on the corner of West Colvin Street and Midland Avenue. He visits the spot each day and talks to young people about the need to stop the killing.

“The kids are our future. They just want to be heard and (have) someone to talk to,” he said. “I am afraid that I will meet God on Judgment Day, and God will say, ‘You say that you love kids. But what did you do to help them?’ Then he will tell me to take my seat on the other side. This is what motivates me.”

Jelani Jefferson, owner of Wisefire Imports, which sits near the corner where Cannon stands each day, finds that Cannon’s mission is driven by love and hope for change.

“He has a sincere heart about it,” Jefferson said. “He’s just there willfully doing a duty. It’s his way of contributing to the youth and bettering our community.”

Jefferson recalls a conversation he once had with Cannon and how his words made an impression.

“He (Cannon) thinks of the youth in the community as his children. It’s not something he has to say or care about, but he does because he wants to do better.”

Cannon commissioned Picasso, a Syracuse artist, to paint the banners. One banner includes a picture of a casket with the words: “Stop the Senseless Killing of Our Youth.” The other is a picture of a headstone with the words: “Too Many Have Fallen.” Cannon attached an assortment of knives, a replica of a 45-caliber handgun and a pair of handcuffs to the banners.

He completed the display by laying spent gun shells, bullets, a knife and dice at the base of the banner.

He explains the concept.

“Dice leads to gambling, gambling leads to fighting, shooting and death,” he said.

Three of the five knives came from kids in the neighborhood. They walked up, looked at the banner and gave him the knives. He requested the other two knives from adults in the community to complete the display.

“One day, a lady stopped by and started complaining. She said that I shouldn’t be here,” Cannon recalled. “As she was complaining, a kid walked up and gave me the green switch blade that you see on the ground,” he said.

“After witnessing this, she understood what I was trying to do and apologized. She became one of my biggest supporters. Only God could have made that happen.”

Using the banner to draw attention, Cannon voices his plea to anyone and everyone who will lend an ear. The banner caught the eye of 8-year-old Clintwan Hill one day this summer.

Using the banner to draw attention, Cannon voices his plea to anyone and everyone who will lend an ear. The banner caught the eye of 8-year-old Clintwan Hill one day this summer.

“Why do you have the gun there?” Hill asked.

“Gun equals casket,” Cannon said. “I took that gun from a boy your age.”

“Is it real?” Hill asked.

“No,” Cannon said.

Hill wants to be a police officer or FBI agent when he grows up to help his community. Cannon praised him and told him that he is on the right track. It is these types of successful stories that makes Cannon remember why he started this mission. He describes the day when a disgruntled boyfriend of a next-door neighbor decided to kill his girlfriend. Cannon’s mother was visiting the neighbor when the man pulled out the gun and shot Cannon’s mother twice. Cannon said he put his arms around his mother in an attempt to pull her from danger. The man turned his gun on the girlfriend, who attempted to run. After being shot several times, she fell to the floor — and her life was finally taken with  two fatal shots to the head. His mother died as well.

two fatal shots to the head. His mother died as well.

“I used to ask God why he let this happen. I was angry for a long time. That happened when I was 10. I’m 40 now. I turned tragedy into a lesson. I channel the anger to do this,” he said.

“I miss her, but she gave me enough memories to last a lifetime,” he added.

Cannon also bears in mind the killing of “little Jason” Willis, whose funeral he attended in July.

Cannon recalls seeing 18-year-old Willis and eight other young men riding their bikes on the night Willis was killed. He spoke to them and asked them what they were doing out.

“Jason was a good young man. He was always respectful to me. He wasn’t a street kid. His friends were in the street,” he said.

Jason’s death motivates Cannon to keep pushing with his campaign.

“I can’t understand why other fathers haven’t joined me on this corner,” he said.

Reshana Blackshear, a family support specialist and resource center advocate at the People’s Equal Action and Community Effort (also known as P.E.A.C.E.), agrees with Cannon.

“We need more of him,” Blackshear said. “His initiative of one child at a time is a beautiful thing.”

Blackshear points out that it’s a difficult thing for the youth in this community to open up and be communicative. To have a figure like Cannon, as Blackshear notes, can only begin to break down walls and encourage young people to take a stand against violence.

“He’s setting a pathway of positive initiative for the youth and others in the community around here. It’s really amazing.”

While Cannon stands alone each day, he is hopeful that others will begin to share in his cause. Until then, Cannon vows to continue his one-man fight to stop the killing — the lone voice crying in the wilderness on behalf of the children.

— Article by Keith Muhammad, The Stand Community Correspondent; additional reporting by Natalie Caceres, The Stand staff reporter

The Stand

The Stand