Community members and transportation officials examine I-81’s role in Syracuse

Years before President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway System spread across American cities and eventually through Syracuse, the city’s 15th Ward was a vibrant, diverse community. Within it were high- and low-income residents, white and black neighbors and the city’s first black dentist.

But in the 1950s and ’60s, the largely African-American community was razed to make way for an elevated interstate highway that would displace nearly 1,300 residents to the South Side. Whites took to the suburbs, leaving abandoned buildings in their wake.

No one asked the community what it wanted when I-81 was built 50 years ago, said James D’Agostino, director of the Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council, the organization responsible for Onondaga County’s transportation planning.

No one asked the community what it wanted when I-81 was built 50 years ago, said James D’Agostino, director of the Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council, the organization responsible for Onondaga County’s transportation planning.

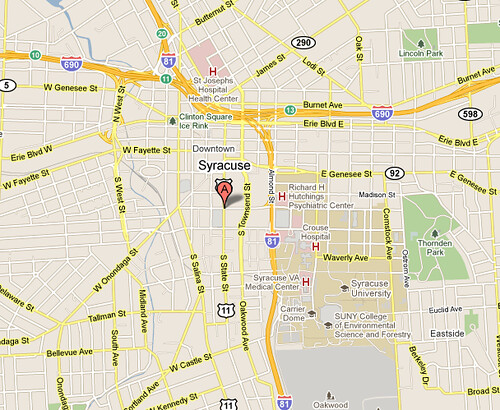

Today, portions of Interstate-81, the expressway that cuts through Syracuse, are nearing the end of their lifespan. The visibly decaying viaduct, the 1.4-mile elevated strip, prompted the transportation council and the New York State Department of Transportation to launch The I-81 Challenge, a public outreach campaign to address the future of I-81 in the next decade.

“We’re in some ways tripping over ourselves to involve the public and make sure people know about this project so that no one feels that this is being done in a back room behind a closed door,” D’Agostino said.

The I-81 Challenge has a website, blog and Facebook page with case studies, newsletters, fact sheets, maps and a questionnaire available. The state agencies will hold the first round of public workshops in early May to inform the community of all the options, he said.

After thorough analysis of I-81’s physical conditions, D’Agostino said it became clear something had to be done. Options include burying or depressing the highway, relocating it, replacing it with a boulevard or simply maintaining it as is.

“We had to ask, OK, do we just pour tons of money into maintaining something that is close to the end of its life?” D’Agostino said. “We thought we should get ahead of it and get the community involved to determine what works best for Syracuse today and in the future.”

Memories of I-81’s construction and stories told by parents and grandparents linger in the minds of South Side residents. The interstate is a barrier to the rest of the city — physically and symbolically — community members have said.

“It impacted low-income communities more than other areas. That’s pretty obvious,” D’Agostino said. “A lot of people were displaced because of I-81, but it wasn’t the only factor. Whether it being a barrier is real or perceived, that’s something we’re going to look at.”

Walt Dixie joined the challenge’s Community Liaison Committee, composed of 37 local organizations, to make sure the future of I-81 doesn’t segregate communities. As executive director of Jubilee Homes, a local corporation that works to revitalize housing and economic development of the Southwest side, he said it’s his job to bring the historical perspective of the South Side to the discussion.

“Whatever 81 becomes, there should be a larger version of the 15th Ward, in terms of true diversity and ownership,” Dixie said. “We need a vibrant city. We don’t need a gated community.”

“Whatever 81 becomes, there should be a larger version of the 15th Ward, in terms of true diversity and ownership,” Dixie said. “We need a vibrant city. We don’t need a gated community.”

Getting the community involved

Prior to The I-81 Challenge, NYSDOT and the transportation council held 23 focus groups in the community to discuss preliminary concerns. But many South Side residents didn’t realize what was being done because they were never engaged in the process, Dixie said.

“It’s important that you bring that diverse population together to sit at the table so it truly reflects that,” Dixie said. “And I think they have a ways to go with that. That’s why we’ve got to make sure we have all the right actors and participants at the table before they even start talking about options.”

D’Agostino said anyone on the South Side who asked to be involved in the process was included. He said he hopes more residents come to the May workshops so they can share what they need for the neighborhood.

A Syracuse resident all his life, Dixie said he has witnessed the South Side become a vacuum, to some extent because of I-81.

“You can’t just continue to condense buildings and keep a certain income population impacted together,” he said. “You need to diversify people, diversify businesses and celebrate your history at the same time.”

Bill Egloff, NYSDOT’s project planning manager, was surprised to hear similar desires expressed for the future of I-81. City and suburban residents, stakeholder groups and others told him they recognize that the vitality of the city is important to Central New York.

“They all said that what they wanted to see different was that the burdens and the benefits were shared — unlike the feeling of the minority community, who bore the brunt of what happened 50 years ago,” he said.

Also a lifelong Syracuse resident, Egloff said he remembers when Syracuse University was referred to as “those folks on the hill,” after the interstate was built. He understands the perception that I-81 separates University Hill from the rest of the city, including the South Side.

In combing through case studies, NYSDOT was certain that public participation was the key to a successful project, he said.

In combing through case studies, NYSDOT was certain that public participation was the key to a successful project, he said.

“No matter what community it was, the success of whatever option they implemented was tied to the intensity and the transparency of their public outreach,” Egloff said. “Everybody says that public participation is crucial, and we recognized that early on.”

Some residents want to leave I-81 the way it is. Ron Williams wakes up every day and sees the interstate from his window on the 21st floor of Toomey Abbott Towers.

“It’s part of my décor. Imagine that view,” he said.

The interstate should be left alone, said Williams, who describes 81 as the best thing that ever happened to Syracuse. He acknowledges that the highway is old and brittle, and that it needs to be repainted and maintained in certain areas. But he says there is no reason to tear it down, relocate it or rebuild it.

The 57-year-old painter and carpenter said the interstate contributed to the success of urban renewal in the area and is a source of pride for the community. It brings people into the city, through the city and back out of the city, he said.

“You’ve got a highway smack-dab in the middle of the city. What else do you want? Highways going around the city? In the back of it? This does the same thing, but it goes right in the middle of the city. You can look at what’s in the city. You get at the top of the mountain in the city and you can look directly into the city from 81. It’s beautiful. It’s breathtaking.”

Ultimately, residents should play the largest role in whatever decisions are made about I-81, Williams said. Many people don’t know what has been discussed so far, he said.

“Everyone needs to come together and make a decision on this,” Williams said. “You have a lot of guys with their hats in the ring that are just laying back dormant and saying, ‘Whatever you want to do.’ And that’s not fair to the residents or to the business people in the city.”

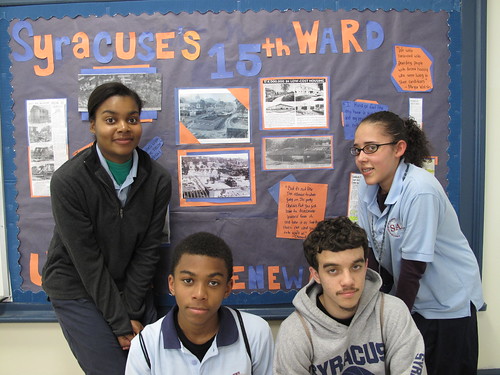

Some see the controversy over the interstate’s history and its current conditions as a teaching experience. When Nicolas Salibrici told his class at Syracuse Academy of Science Charter School that they were going on a field trip to the library, he was met with blank stares. “They looked at me like I had three heads,” he said.

But as the ninth- through 12th-graders combed through microfilm and Syracuse newspaper clippings from the 1950s and 1960s, they wanted to stay longer than time permitted.

“They were just completely immersed, and I think a little awestruck by the sense of history at their fingertips,” said Salibrici, who is educating his class on I-81, urban renewal and the history of Syracuse’s 15th Ward.

Involving young people in the process is crucial, said Dixie, executive director of Jubilee Homes. The focus meetings missed the opportunity to hear a young perspective, he said.

“How can you do a design that will be around for the next 30 or 50 years and not include the young kids?” he said. “Kids should play some role for the future.”

Salibrici hopes that by the end of the school year, the class will have a plan in place to address the future of I-81. The hands-on interaction of the class project makes it the first “authentic and experiential” education of Salibrici’s 10-year teaching career. He said the students, who live all over Syracuse, feel empowered by their involvement.

“We want to be involved with the dialogue about I-81 and what should be done and what could be done to help correct the mistakes that the city made 50 years ago when they didn’t involve the community,” he said. “We want to be a part of that process, to empower the students and give them a voice and let them tell the city what they think.”

The Stand

The Stand