Community members rally to overcome challenges as the Dunbar Center loses funding

Adalsa Latty points out the window of his ground-floor office at the Dunbar Center. A snow-speckled South State Street outside is cracked and rundown, cutting through a struggling neighborhood. He drops his hands in despair. He sighs with the force of someone exhausted after a long battle.

“Sometimes when you come here, you see cars lined up from here down to the next block,” Latty says, looking out the window. “They come for service. They get service. I don’t think anybody has ever come here for help and they don’t get it.”

As an after-school supervisor at Dunbar Association, Inc., a 92-year-old nonprofit that largely serves the local black community, Latty has seen children and parents in need of help. But that help could be hard to get come July when Dunbar will no longer receive $200,000 in funding from United Way of Central New York, about a quarter of Dunbar’s $999,720 budget.

“I don’t see the necessity for the cut,” said Latty, who has been with Dunbar for eight years. “I can’t see why. I really don’t know why. Why would you cut funding when children are learning? What is it you’re doing really?”

Dunbar helps more than just children. With its 25 employees and 15 volunteers, Dunbar provides outreach programs for the elderly, teen mentoring, after-school youth programs, and family and adoption services. But the center has been burdened with declining revenue and a thin base of support over the years, prompting a recent reorganization of its administrative staff.

The local United Way, which funds 38 nonprofit agencies in Onondaga County, was forced to decrease its funding for Dunbar a total of 10 percent in 2008 and 2009 because of the recession, said Frank Lazarski, president of United Way of Central New York.

Dunbar did not pass a fiscal and management review, Lazarski said, and in turn was not invited to participate in United Way’s next three-year funding cycle, beginning July 1. He cited concerns about Dunbar’s efforts to bring in new revenue, its lack of a well-organized development plan and low attendance at board meetings as reasons its funding was cut.

“You can’t just say, ‘We’ve gotta raise more money.’ You have to organize yourself, and we found that that just didn’t happen,” Lazarski said. “They need hands and feet over there and people helping them out. For too long, they’ve struggled with lack of help.”

Louella Williams, who had been president of Dunbar’s board of directors, recently became executive director when Sharon Jack-Williams stepped down from that position; she declined to comment on her temporary move to executive director. Jack-Williams could not be reached for comment. Louella Williams said Dunbar already has reorganized its board; Steve Williams, who had been vice president, recently took over as president.

Several new members to the board are Dunbar alumni. Dunbar was their place growing up, Louella Williams said. It gave them their start.

In February, Williams said the city increased funding to Dunbar’s neighborhood program from its Community Development Block Grant, a federal program that supports low-income neighborhoods.

The community refused to let Dunbar’s doors close, Williams said. “It really sort of brought people out of the woodworks — people who were just sitting down and just doing nothing,” she said. “It has really brought them out. And a lot of Dunbar’s alumni woke up and said, ‘We have to do something to keep Dunbar at the forefront.’ ”

Dunbar can reapply for United Way funds in 2013. In the meantime, it is working with the YWCA Syracuse & Onondaga County to continue several of its programs.

The YWCA and Dunbar have had a relationship for a little over a year, said Joan Durant, executive director of the YWCA. When United Way announced the cut, the YWCA submitted a collaborative funding proposal — currently under review — for the two organizations that would allow several Dunbar programs to operate under the YWCA umbrella.

“We saw a real fit for our missions to work together, so it didn’t seem a real stretch to do this,” Durant said. “We’re very familiar with the South Side and the programs and the needs there. And we wanted to make sure these services were still being provided in that area.”

United Way funding pays for more than half of Dunbar’s after-school program, which Durant hopes the YWCA can help keep afloat.

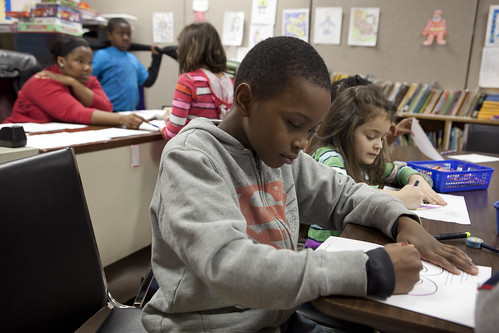

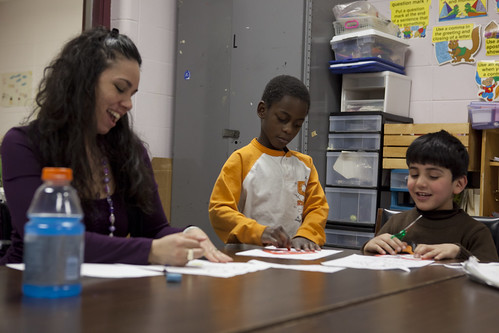

When the children arrive at Dunbar every day, the first thing they do is homework: math, English Language Arts, writing. But homework isn’t all the program does.

In the back of a toy-filled classroom, plastered with nutrition posters and artwork, Javonna Procks gets out of her chair and twirls the pendant of her necklace. With each tap of the pendant on the chair, Procks smiles.

“People used to play with these when the Erie Canal was made,” said the 9-year-old student of Van Duyn Elementary School on Loomis Avenue, admiring her necklace. “I think it’s very interesting.”

Procks learned about the necklace and the Erie Canal on a field trip with other children from Dunbar. The children have visited Syracuse University, Paradise Market on Erie Boulevard and the Rosamond Gifford Zoo.

In a classroom down the hall, Latty quizzes four students on science, health, geography, math and English. He explains to them that guessing on true or false questions rarely works.

Latty said he’s thankful for United Way’s help in the past, but he wonders if it could be doing more now.

Dunbar will continue to do what it can out of the little it has, he said.

“Dunbar will remain Dunbar,” Latty said. “God has his time for doing things in a way that we might not be pleased with because we don’t understand what God has given to us. So we are upset about it. But it’s a process. It takes time. It takes faith, and that’s what we have.”

The Stand

The Stand