Survey shows students’ view of police changes at the schoolhouse doors

Syracuse city students tend to have positive interactions with police officers stationed in their schools, according to a survey conducted by the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. But the survey found that those attitudes change when teens deal with officers outside of that setting.

The survey also found that black, Latino and Asian respondents were more likely than white students to agree with the statement that police unfairly target minorities.

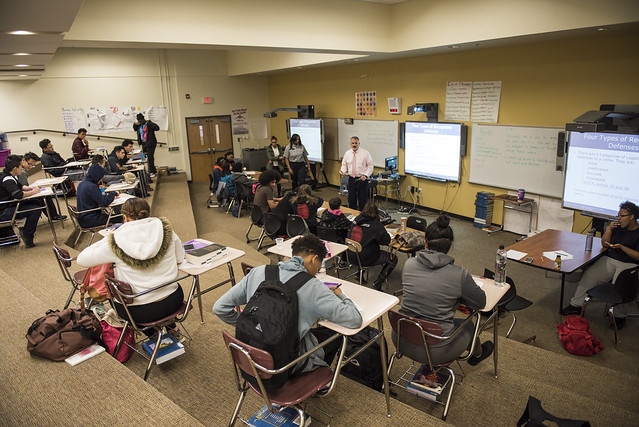

The survey asked respondents 40 questions in all about their interactions and experiences with police officers and law enforcement. A total of 184 students from four different high schools in the Syracuse City School District completed the survey in their government classes last school year.

The survey results cannot be said to represent the views and experiences of all Syracuse students for certain, but they do offer reasonably accurate insight into the experiences of many of them.

Ninety-five percent of respondents were seniors and 86 percent were older than 17. Fifty-two percent of those who took the survey identify as black, 15 percent as white, and just over 10 percent each as Latino or Asian.

Ninety-five percent of respondents were seniors and 86 percent were older than 17. Fifty-two percent of those who took the survey identify as black, 15 percent as white, and just over 10 percent each as Latino or Asian.

As a whole, the city of Syracuse population is about 55 percent white, 29 percent black, 8 percent Latino and 7 percent Asian, according to the 2015 American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau.

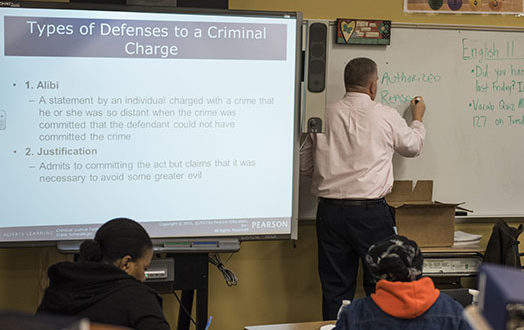

Students were asked 13 questions relating specifically to their interactions with officers assigned to their high schools — known as resource officers.

Just 5 percent of respondents said the officers’ presence on school grounds made them feel uneasy, compared with 48 percent who said the officers made them feel safer.

“The police in our school are kind,” a 19-year-old female from Corcoran High School said in the survey. “They do everything they can to keep us safe and in a good mood.”

Almost three-quarters of respondents said they knew the name of at least one officer who worked in their school and 94 percent responded that an officer had helped, or offered to help, with a problem that had arisen. Ninety-five percent of students said an officer had engaged them in a personal conversation on at least one occasion.

“The police in my school are very good people,” one 18-year-old female Corcoran High School senior wrote in the survey. “They don’t always try to be aggressive but they try to make us as safe as possible. They do their jobs!”

Anthony Davis, the Syracuse City School District’s assistant superintendent for high schools and career tech education, said that the number of resource officers stationed at each school varies by student enrollment. Davis estimated that two officers and six to eight school sentries — monitors responsible for patrolling the hallways — are on duty at one time in Henninger High School, Syracuse’s largest with 1,745 students. In total, 19,951 students are enrolled in the district, according to the New York State Education Department.

Davis said he was not surprised by the students’ positive responses regarding resource officers.

“They are doing some of the preventive measures that will keep kids from getting into a situation where something is illegal,” Davis said. “I think in that sense they may be seen as a positive resource versus someone who is constantly after them for something that they’ve done wrong.”

Delores Jones-Brown, the founding director of John Jay College’s Center on Race, Crime and Justice, has conducted extensive research on police-community relations and juvenile justice. She said students become more trusting of police officers when they begin to know them on a personal level.

“(I’ve found that) the symbolic police officer is something that young people might not care for,” Jones-Brown said. “But, when they have an opportunity to interact with the police on a non-intrusive basis, they can see that the individual police officers are OK.”

Student responses changed when they were asked about their feelings toward — and interactions with — police officers outside of school.

Davis said this shift was most likely caused by the environment in which students deal with the officers.

“Once you’re in a school, the officer isn’t the primary source,” Davis said. “They are not directly in charge. They only take over if the building asks them to, or if they see something illegal. So, they have means to create relationships. On the street, once they are called, they’re in total control from that moment. I think they come in with a different attitude, one of self-preservation that nothing happens to them.

“I’m not saying that the situations that the officers have to deal with are always easy or simple. These things are very complicated. But, I think our kids are simplifying it, and they feel like there is wrongdoing at times and they are internalizing that.”

Just 36 percent of all respondents said that they somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement, “I trust the police.”

That number shrank to just 29 percent of students who identified as black or Latino, while 58 percent of white respondents and 63 percent of Asian respondents somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement.

“I’ve had almost no direct contact with police,” said a female 17-year-old senior at the Institute of Technology at Syracuse Central. “But, I generally do not feel safe around them out of fear that they may assault me.”

Forty-seven percent of students indicated they somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement that police unfairly target teenagers, and only 30 percent said that they felt as if the police trusted them.

Forty-seven percent of students indicated they somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement that police unfairly target teenagers, and only 30 percent said that they felt as if the police trusted them.

Fifty-nine percent of black, 53 percent of Asian and 52 percent of Latino respondents said that they somewhat or strongly agreed that police unfairly target minorities. Just 25 percent of white students who participated in the survey responded in the same way.

Jones-Brown said that students may feel more positively toward the officers in their schools because of the consistent interactions they have with them.

“Because the officers are encountering the young people on a daily basis, there’s not that fear based on the unknown,” Jones-Brown said.

“Too often (officers) are being trained to think that they are going to be under attack. They don’t understand that when they start out in an agitated state, then it agitates the civilian. I think that the familiarity that the (resource officers) have with the students reduces stereotypes, specifically negative stereotypes, and reduces the level of fear that would be involved in interacting with a young person.”

Forty-seven percent of respondents said they had been a passenger in a car that was pulled over by the police, while 9 percent said they had been the driver of a vehicle that was stopped.

Two-thirds of students, however, responded that they had never spoken with a parent or other adult about what to do in that situation or if they are approached by an officer on the street.

John Klofas, a professor of criminal justice at the Rochester Institute of Technology and director of The Center for Public Safety Initiatives, said he would have expected more students to have had this conversation with an adult or authority figure.

“These concerns in many ways are very prevalent in the minds of young people and presumably the minds of parents,” Klofas said. “Over the years I’ve spent a lot of time talking to people about this very issue.”

Davis said this could be because many students in the district rely on peers for information.

“I don’t know if our kids today are conscious in having those conversations,” Davis said. “I think the anger and perceptions are so deeply woven into their experiences that to have those conversations would be difficult for them. I think they don’t know how to handle their emotions, so therefore you don’t talk about it and I think that is extremely problematic.”

— Article by E. Jay Zarett, They Wear Blue reporter

The Stand

The Stand