After many life battles, Damon Gilstrap defies all odds

On his first date with the woman who would become his fiancé, Damon Gilstrap detailed his entire past — the group homes, the drugs, the violence, being homeless and time incarcerated.

He was completely transparent.

“I didn’t know if he was trying to run me away or what,” said Angela Wilson, who added that looking

back on that evening, it was not typical first-date etiquette. “But he told me, ‘I’d rather you hear about my past from me, than from someone on the street.’”

Wilson admired him for his openness and said she found him intriguing and someone she could build a life with. That life has now spanned 17 years — in sickness and in health.

THREE BRAIN TUMORS

Ten years ago, Gilstrap suffered a stroke as a result of three benign brain tumors. Wilson remembers the night she found him on the couch, speaking gibberish. “I took it as sleepy talk,” Wilson said about the unrecognizable drivel. “The next morning, he was talking the same way. When he stood up, he was all wobbly like a baby deer.”

Despite his objections, she rushed him to the hospital.

The three tumors were positioned around his brain, pressing into areas that control motor function and speech.

Just months before the stroke, Gilstrap had been found wandering the street disoriented, naked and combative. Police restrained him and took him to the hospital, admitting him as a John Doe.

Doctors ran tests, diagnosing him with meningitis. He bounced back quickly, says Wilson who did research on the disease, learning it can be fatal. She said she kept an eye on him, but they quickly resumed their regular routines. A week after being hospitalized with the infection, Gilstrap returned to work cutting grass and performing other maintenance duties with Syracuse Housing Authority, where he had worked for 20 years.

“We’re not 100 percent that the tumors were separate and came after the meningitis,” Wilson said. Doctors explained that his type of tumors can remain dormant. “But it seems three brain tumors can’t just happen from Thanksgiving to January.”

Hearing that the tumors were benign was a blessing. But the news was shocking. Wilson says his diagnosis left her in denial. “We’d been together for seven wonderful years and now get this devastating blow,” she said. At that time, she was 35 and Gilstrap was 40. As their life grew together, such a major health scare — a second one — was more than unexpected.

“We learned the tumors weren’t growing, but were actually shrinking,” she said.

Now, the three masses have shrunk to the point where they are no longer a concern, but the effects from the scarring on his brain remain. Doctors told the couple: This is his new normal.

BEATING THE ODDS

After the stroke, Gilstrap remained in the hospital for a week; then staff encouraged Wilson to move him into a nursing home.

He adamantly refused, telling Wilson: “You know my story. I’m going to beat this.”

She told him — all 6 feet 3 inches of him — that he was not to fall on her, and he would have to make it to the bathroom. “If you fail even once, I’ll send you off to the home.”

Gilstrap proudly confirmed, “I never fell and had no ‘accidents.’”

Wilson enlisted a team of 10 — close family and friends — to provide around-the-clock care.

“The village came through,” she said.

ROAD TO RECOVERY

Months after the stroke, Gilstrap would get dizzy and walked with a cane. He kept on a physical therapy schedule to build strength. “While Damon was able to do some things, he was not able to do what was needed at his former job,” Wilson said. He went on workers comp for a year and then was deemed permanently disabled.

“Doctors told me I would never talk. I would never walk … that I would never do a lot of things again,” Gilstrap said. “But I proved them wrong. I’m walking. I’m driving. I’m talking … a little different, but I can still talk and have my mental faculties.”

After graduating from his prescribed physical therapy, he continued to push himself. “I turned the backyard into an obstacle course to relearn to walk and build my coordination,” he said. “Everything the hospital told me I wouldn’t do again, I would practice.”

Wilson says Gilstrap would repeatedly do coordination moves like running in place, to regain use of his left side because it had been compromised by the stroke. Doctors also encouraged him to join a gym for the social aspect because the stroke immobilized his left vocal cord, which made him self-conscious when talking.

Initial recovery was slow. He could not pick up a coin with his left hand or feed himself.

A friend became his personal trainer. Gilstrap started with 10 pounds and worked his way up to get his left side as strong as his right. “I would practice for hours and hours, and now I lift weights on my own at the Y regularly,” he said.

SILENT PROMOTION

“If he gets excited, then he speeds up (his speech),” Wilson said. “I can tell no one is understanding him. They get a little smile on their face and just start nodding. Once he gets talking too fast … I can see the disconnect.”

“If he gets excited, then he speeds up (his speech),” Wilson said. “I can tell no one is understanding him. They get a little smile on their face and just start nodding. Once he gets talking too fast … I can see the disconnect.”

Doctors tried to expand the opening and aid his speech by injecting Gilstrap’s left vocal cord with calcium. The couple watched the procedure on a TV screen captured by a camera that doctors had slid through his nose. The up-close view confirmed his left side is paralyzed.

“The right one was just going to town, vibrating like crazy,” Wilson said. “But his left looked like it was saying, ‘No I’m good. I’ll just stay still and hang out over here.’”

The procedure offered limited relief. The existing damage is irreversible, Wilson said. “His speech will forever be impacted.”

While his speech did not hamper his physical recovery, it did prevent Gilstrap from engaging much socially and from promoting a book he had started writing about two years after his stroke.

His close friend, Greg Hall, kept telling him he had a hell of a personal story, and he should stop hiding and share it with people.

Hall and Gilstrap met in 1999 at ‘410’ — short for 410 South Crouse, the Chemical Dependency Treatment Services center run by Crouse Hospital. Both were attending narcotics anonymous meetings, and at that time, Gilstrap’s reputation was as a drug dealer.

Gilstrap explains he turned to selling drugs as the best way to provide for his family. His book details how he tried legitimate jobs, but could best provide for his four children — and even help others cover their rent or bills — by selling drugs.

“He’s like a family member to me,” Hall said, noting Gilstrap has helped him many times with a place to stay, a meal and more. “Too often I’ve gone back to drugs … and not been there when Damon needs me. I have vowed not to go back that way.” He adds he now wants to push Gilstrap because he believes his friend’s story can help others.

“The reason I help him now is because he’s always helped me,” said Hall, who regrets drifting away from Gilstrap in years past. “He’s never given up on me.”

In 2014, Gilstrap’s autobiography “From Tragedy to Homeless to Triumph,” was published. Gilstrap spent three years writing it as a way to reflect on his troubled past. He said he felt forced to make certain decisions in order to survive while he grew up in the system, describing his youth as being “warehoused,” bouncing from group homes to the streets of Washington D.C.

In 2014, Gilstrap’s autobiography “From Tragedy to Homeless to Triumph,” was published. Gilstrap spent three years writing it as a way to reflect on his troubled past. He said he felt forced to make certain decisions in order to survive while he grew up in the system, describing his youth as being “warehoused,” bouncing from group homes to the streets of Washington D.C.

“We had to turn from sheep to wolves in order to survive,” Gilstrap writes in his book, describing the childhood he shared with his brother.

Writing was not easy for him. At that time, his education went to about a fifth-grade level and drafting his book required nearly constant stops to check spelling or ask about a word.

“I didn’t know anything about run-on sentences,” he said. “And if I didn’t know a word, I would even call my brother and ask him to spell it to me.”

He was so excited and kept talking about this book, Hall remembers. “I didn’t have the courage to tell him I didn’t think he could do it, and good thing I didn’t, because I would have been wrong.”

GREATER LATER

After the book release, Gilstrap did one book signing. But the hype faded quickly because he was so uncomfortable with how he spoke.

“He was insecure,” Wilson said.

With encouragement from family and close friends, Gilstrap has recently changed his mind and is stepping out to share his story. He also says he has completed a second book.

“The second focuses on how I defeated brain tumors and now use my head rather than violence,” he said. “I want to show people how I became a homeowner from once being homeless.”

But the second book will not be released just yet, Gilstrap says, because he wants to ensure it has no mistakes. Currently he’s working to earn his high school equivalency degree by working with tutors at the Syracuse Educational Opportunity Center (EOC) four days a week. He also completed a writing course with the YMCA’s Downtown Writers Center.

“If I get my education,” he said. “I know I can make my next book even better.”

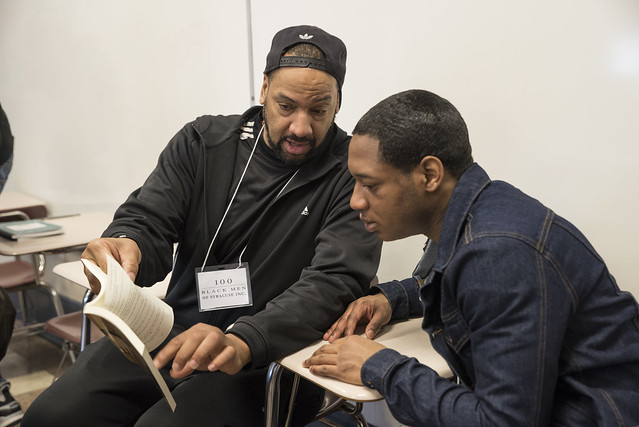

Returning to school is also a way for him to encourage youth whom he mentors. Gilstrap has served as a mentor with the 100 Black Men of Syracuse, Inc., for the past two years and with The Grace Project for three years.

The Grace Project works with teens in jail and also with those who recently have been released. The young men have a hard time breaking out of the cycle they are in, and many don’t have their high school degrees, says Dr. Sarah Reks, an outreach member.

Reks has known Gilstrap since he joined the Grace Episcopal Church’s jail ministry, which she has been a part of since the project’s inception in 2013. She notes Gilstrap adds so much to the program by connecting to the young men — the majority of whom are also African-American — and relate to Gilstrap’s traumatic youth. She says his story demonstrates how someone can change — not having to be defined by one’s mistakes.

“Having a black man who can model and mentor to them is critical,” she said. “It’s incredible how Damon is serving as a role model not only by sharing his experiences but by working toward earning his degree.”

Even at the age of 50, she adds, he is displaying that desire to better himself.

Gilstrap explains why he works so hard.

“I say, how can I tell these kids to stay in school if I haven’t done it. If I don’t finish, how can I tell them to do it?”

— By Ashley Kang, The Stand director

Watch Video On Gilstrap produced by NPPA Multimedia Immersion

Guy Wathen – Greater Later – NPPA Immersion 2015 from Multimedia Immersion on Vimeo.

The Stand

The Stand