Workshop explores native birds and environmental effects on community

What is now known as the South Side was originally a forest periodically flooded by a meandering Onondaga Creek. The indigenous population in this region survived by hunting, fishing and gathering. This changed, first, when settlers moved in and, later, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers canalized the creek. These actions had some advantages but also costs, one of which was weakening the connection between human residents and nature.

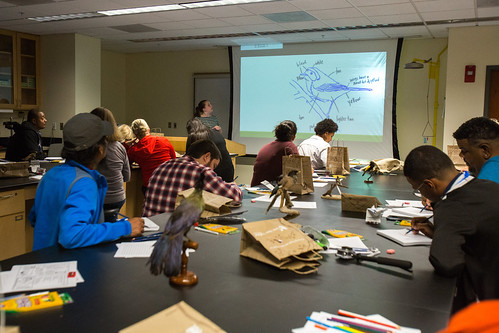

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology is trying to bridge the current gap between urban dwellers and nature. It recently offered scholarships for community advocates and grassroots leaders from low-income communities, such as the South Side, to attend a workshop on its campus.

To view even more photos from the workshop, visit here

The goal of the workshop, held Oct. 18 and 19, was to “expose participants to cutting-edge conservation science and inspire them to engage their communities in citizen science and community-based stewardship projects,” according to a press release.

After a national competition, two Syracuse residents (including this correspondent) won spots in the final selection of 18 participants. Other attendees hailed from Brooklyn, California, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, Oklahoma, Oregon, Tennessee and Puerto Rico.

Marta del Campo, the lab’s outreach specialist, is part of the Celebrate Urban Birds (CUB) Team, along with Karen Purcell and Marilu Lopez Fretts. At a dinner for workshop attendees, del Campo said that up to 500 applications are received from across the country for workshops of this kind.

Lab researchers say that our avian counterparts can play a role in reconnecting urban citizens to nature.

In the case of the South Side, the clearance of the forest dramatically transformed the landscape along Onondaga Creek. But remnants of a forest environment can still be found in this neighborhood in the form of descendants of the native birds that once soared over the trees’ canopies. Among them are peregrine falcons, an endangered species, as well as the more common crows, robins and doves. Showing extraordinary resilience, these feathered creatures were able to adapt to the destruction of their natural habitat and live year-round on the South Side once it came into existence.

“Birds can be a gateway drug to nature,” Charles Eldermire, a Bird Cams Project leader at the lab, told the workshop audience.

Jennifer Shirk, director of field development for the Citizen Science Association, another lab program, also addressed the attendees. Her message: Birds bring benefits, such as pest control and aesthetic value, to the Homo sapiens species.

But Edward Morris, who is a professor in the department of transmedia at Syracuse University, suggested that it should not be a one-way street. He broadened the issue from just “How do we look at animals?” to include “How do animals look at us?” In the spirit of President John Kennedy’s inaugural address in 1961, this could be translated into: “Ask not what the birds can do for you, ask what you can do for the birds.”

The mission of Cornell lab seems to be consistent with this noble aspiration.

“The Celebrate Urban Birds project evaluates the significance of green spaces for birds,” Purcell said in her welcome speech. “Greening the city would benefit both humans and birds.”

Miguel Balbuena, a South Side resident, and Anton Ninno, a teacher at Southside Academy Charter School, won scholarships to attend the workshop

The Stand

The Stand