Rashawn Sullivan is on a path to redemption after killing another South Side teen in 1997

“Slow” is how anti-violence activist Rashawn Sullivan described the day he ended 18-year-old Jason Crawford’s life — the same day that launched Sullivan’s apologetic journey.

“I, now, believe Jason’s death was a sacrifice for me to bring a level of awareness to the world about being apologetic and about the damage that violence can do not only to yourself, but to individuals and to your families,” Sullivan said.

On March 9, 2015, Sullivan was released from Cayuga Correctional Facility after serving 17 years for committing a drive-by shooting on the corner of Wood Avenue and South Salina Street. Less than a year after his release, Sullivan organized a vigil in Crawford’s honor to apologize to his family — and also to advise others to avoid violence.

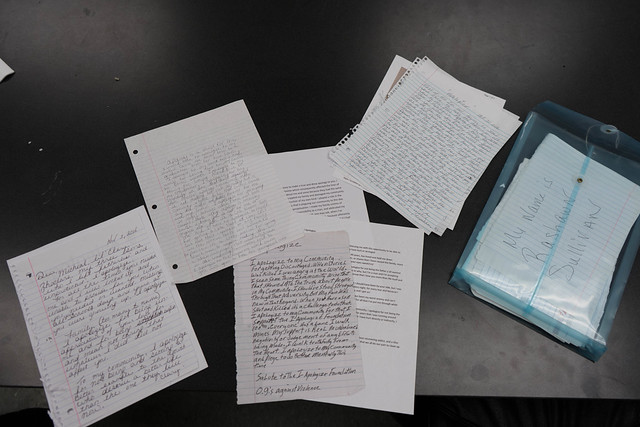

Sullivan read aloud an apology letter while crying tears of remorse for the pain he had caused. In news coverage of the public apology, Crawford’s cousin, Delaine Crawford Hills, can be seen hugging Sullivan at the vigil. She accepted his apology and told him to continue to do positive things.

When Sullivan had been sentenced, Crawford’s relatives packed an Onondaga County courtroom seeking an apology from the teenage Sullivan. Reports in the Syracuse Post-Standard from Sullivan’s sentencing before Judge J. Kevin Mulroy in 1998 say Sullivan offered no apology or explanation as to why Crawford was shot. Crawford’s sister, Jackie Crawford, was reported to have told a reporter after the sentencing that Sullivan is likely suffering for what he has done “even if he won’t show it.”

PATH TO APOLOGIZE

At some point during his time in prison, Sullivan began to feel remorse and seek forgiveness. Today, Sullivan, 36, continues to combat violence affecting the Syracuse community through his public speaking and outreach. He hopes to fortify the community by telling the story of his apologetic transformation. Through his iApologize Foundation, he wants to inspire others to take responsibility for their actions.

“His approach is very targeted,” said Sharon Owens, CEO of the newly renamed Syracuse Community Connections housed at the Southwest Community Center. She says she has seen others seek forgiveness from society or their community, but says Sullivan is different because he reached out directly to the family affected. She says some families are not receptive and never again want to see the killer of one of their family members. “But many in the community still understand (the iApologize) sentiment and are supportive of his efforts.”

“His approach is very targeted,” said Sharon Owens, CEO of the newly renamed Syracuse Community Connections housed at the Southwest Community Center. She says she has seen others seek forgiveness from society or their community, but says Sullivan is different because he reached out directly to the family affected. She says some families are not receptive and never again want to see the killer of one of their family members. “But many in the community still understand (the iApologize) sentiment and are supportive of his efforts.”

Sullivan said he uses the iApologize organization, which received a business certificate in 2015 and is currently pursuing nonprofit status, to “raise the consciousness of my people who are ignorant and living a life of destruction.” iApologize started with Sullivan giving a public apology, but has grown into encouraging others to take responsibility.

“For him to say ‘I know my role in creating community violence’ and then work to combat that — I think what he is doing takes a lot of courage,” Owens said.

One major focus for Sullivan now is helping local youth. Last year, he arranged for 50 children to go to Washington, D.C., to attend the Justice or Else gathering. In October, he and his friend, Davon Hunter, took another set of children to Howard University. The trip was funded by community donations. Sullivan helped because he wanted to inspire local youth and present options for the future.

“I wanted to show them a different reality, that you can make the right choices to move forward in a prosperous manner,” he said.

Sullivan previously worked with students at Dr. Martin Luther King Elementary School as a mentor with the Trauma Response Team. He still works with that team to help advocate for community violence prevention. He often can be found at the Southwest Community Center interacting with youth there.

Owens explained that anyone who works or volunteers at the center must first complete a background check. In the background check, individuals with child abuse or sexual exploitation on their record cannot work or volunteer there, she said. While Sullivan does not directly work for the center, the Trauma Response Team leases office space there; all groups with that arrangement also must complete a background check.

Individuals who are returning to the community from prison often go to the center, Owens said.

“Re-entry individuals are going to come back to places that feel like home — and that’s us,” she said. “We don’t want to push away people trying to get back their lives. Rashawn has not re-engaged (meaning engaged with street life). All reports I’ve heard from who he works with and his parole officer is he has not returned to any illegal activity.”

She added, “To be engaged here, you have to be out.”

Owens says the center is there to support young men like Sullivan — those seeking a second chance. Men like him can help others who are engaged in the street or gangs by showing them they don’t want to give up a good portion of their life to prison.

“I overcame darkness and ignorance through a situation that appeared to be bad on the surface,” Sullivan said. “I believe everything happens according to a divine plan, and Jason was part of that.”

THE SHOOTING

In 1997, Sgt. Therese Lore filed a report stating that Rashawn Sullivan, 17, of 204 Landon Ave., and Jonah Seymour, 20, of 2607 Midland Ave., turned themselves in to police and both were charged in the shooting death of Jason Crawford of South State Street.

In 1997, Sgt. Therese Lore filed a report stating that Rashawn Sullivan, 17, of 204 Landon Ave., and Jonah Seymour, 20, of 2607 Midland Ave., turned themselves in to police and both were charged in the shooting death of Jason Crawford of South State Street.

Crawford died of a gunshot wound to the abdomen, inflicted Nov. 25 in front of South Presbyterian Church in the 2000 block of South Salina Street.

Five were driving in a gray Buick that day: Sullivan; Seymour; Tyrone Scott, 17; Jimell L. Godbolt, 21; and Shondell Dayes, 18. Sullivan pleaded guilty to second degree murder, admitting he fired the fatal shot. The others faced weapon and conspiracy charges.

In statements later given by Scott and Seymour, police discovered that Crawford’s killing stemmed from an argument between two South Side groups — and did not involve Crawford. Later during the arraignment, Senior Assistant District Attorney Nicholas DeMartino revealed that Crawford just happened to be walking down the street as Sullivan and the others rode by during an ongoing confrontation with another group.

As reported Nov. 28, 1997 by Jim O’Hara of The Post-Standard: According to Scott’s statement, Sullivan had fired a shot from a handgun at someone else on the street during an earlier dispute. As the suspects drove down Salina Street, they spotted Crawford and another youth near the bus stop. “Then I saw Muscles (Sullivan) raise up with the same gun, a little was out the window and then he fired. I was sitting right next to Muscles, then he fired at the kid,” Scott told police.

The 1997 report also states that Seymour told police Sullivan was involved in a dispute with someone named Andrew over an earlier assault of Andrew’s brother. Sullivan and Andrew were fighting Tuesday (Nov. 25, 1997) when police broke up the fight, Seymour said.

Seymour said he heard a “boom, as in a gunshot” as they drove by the Salina Street area after the first fight. He also said he had seen a gun in the front seat of the car between Sullivan and Scott.

Seymour told police that after they returned to Scott’s home, he heard Sullivan say, “Like, yo. I didn’t mean to hit that kid, yo.”

FAMILY STRUCTURE

Sullivan was raised mostly by his grandmother, Dorothy, due to his mother’s lifelong battle with drugs. He lived in a three-bedroom house with nine other relatives on Syracuse’s South Side. His father was absent during his adolescent and young adult life.

“As a child, you never really look at things like a struggle because your mind doesn’t grasp it. That’s adult thinking. I was just happy to be around my cousins,” Sullivan said of his living arrangement.

He said his “destructive” choices were influenced by his inadequate family structure, as well as by a lack of guidance and education. Yearning for acceptance from his peers on the street, Sullivan said he turned to a life of crime.

At the age of 9, he was sentenced to Hillbrook Juvenile Detention Center for 90 days for robbing former Wayne & Meltzer’s Bike Superstore on Erie Boulevard.

By 11, Sullivan was sentenced to Auburn Residential Center for juveniles for robbing Colonial Laundromat on South Salina Street.

“I wasn’t really equipped to understand what happened at the time. I guess they (justice system) felt I was no longer fit to be in society, so they placed me in there,” Sullivan said.

After three years, he was sent to a group home. But unhappy with the limited amount of time he was allowed to see his family, he ran away. Subsequently, after he was found, he was sent to Tryon Residential Center for juvenile boys.

Education was not a major part of his life, even from a young age.

“I’ve probably had a year and a half of school altogether,” he said, recalling one year of elementary school, no middle school and four months of high school.

During his times in and out of juvenile centers, Sullivan said he never adapted to their education programs because the teachers were not specifically trained to interact with children of his background.

“Initially, I never had the desire to educate myself or worry about my future,” he said. “I was more rebellious because whatever they had to teach me didn’t penetrate the depths of my soul.”

He attended Corcoran High School with a neighborhood friend, Prince Yeboah, before they were both expelled because of behavior issues. “We used to spend every day together,” he said. “When I would wake up in the morning, he’d already be at my house. We were that close.”

He attended Corcoran High School with a neighborhood friend, Prince Yeboah, before they were both expelled because of behavior issues. “We used to spend every day together,” he said. “When I would wake up in the morning, he’d already be at my house. We were that close.”

Yeboah felt Sullivan’s upbringing was the reason he was not able to reach his potential sooner in life.

“His true and honest ability to care has turned him into the man he is today,” Yeboah said.

He recalled a time when Sullivan “saved” him and showed he cared for him. After they were both expelled, Sullivan had no desire to return, yet he understood that Yeboah wanted to get his education. They both went back to school one day — in hopes of getting Yeboah reinstated — when they were approached by some individuals from a prior altercation.

“An argument escalated, and I knew anything that happened at that moment would cause us further harm and me not getting back into school,” Yeboah said.

But Sullivan saved the situation and his friend. Yeboah said Sullivan told him to go inside the school, while he stayed outside and calmed the situation, sacrificing himself.

THE CREATOR

After his first eight years in prison, Sullivan began a journey of self-discovery along with Hunter, his fellow inmate at the time and now close friend.

“It was a moment of enlightenment when our worlds merged,” Hunter said. “I never experienced no friendship like that — this was in God’s plan.”

Hunter says he assisted in Sullivan’s release by seeking influential people to write letters of support on his behalf. “That’s what we do, uplift and encourage each other,” Hunter said.

Sullivan said he began to learn things about himself that he never knew before due to his upbringing — such as he was loving, caring and compassionate. He also began studying conflict resolution and independent studying for astrology, numerology, politics and more. His newfound craving for knowledge stemmed from wanting a better understanding of life in general. In doing so, he found what he calls, “The Creator.”

Sullivan said The Creator told him, “If you want this opportunity (at redemption), then you are going to have to apologize to the family.”

A few days later in the prison recreational area, an inmate told Sullivan that he spoke with great compassion and should start an organization, which today is called iApologize.

He felt The Creator was using him as a vehicle to explain to people what an apology looks like.

“People don’t know what it means to apologize. They think they do, but they don’t.” He adds even something small like cutting someone off in traffic deserves an apology.

“If you’ve done something wrong to someone, just make an open apology.”

— Article by Rachel George, Staff reporter; additional reporting contributed by Ashley Kang, The Stand director

The Stand

The Stand