Residents can attend training to learn how officers make life-and-death decisions

The Syracuse Police Department’s three-day, 10-hour civilian police academy in January 2017 gave 40 community residents some idea of what it is like to make split-second decisions on when and how to use possibly deadly force, and provided the group some legal background, too.

The academy answered some questions for residents, and left them with others.

Chief of Police Frank Fowler told attendees that the academy is designed for residents to better understand how police are trained to respond.

“You will be exposed to the same training as our recruits … and also (learn) how and why we do the things we do,” Fowler said. “Our goal is for you to leave with a more educated eye.”

At the start, officers said they feel current news coverage of police is negative and centers around use of force.

The media has “magnified the bad news,” Fowler said. “But tonight, you will all go home and sleep safely because of these men and women.”

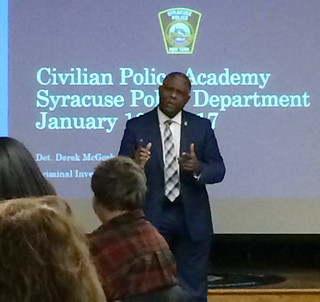

The first night opened with lectures on the laws that govern the SPD, taught by then Sgt. Derek McGork and Detective Mark Rusin. McGork has since been promoted by Mayor Ben Walsh to deputy chief, overseeing the investigation bureau. The second and third evenings included reality-based training exercises, from how to restrain a protester to how to handle an individual wielding a gun.

Brandiss Pearson, a nurse and mother, spoke up as a parent of a black teenager. She said she is concerned daily about her son’s safety. “Having a 16-year-old black son who is 6-foot-2, 260 pounds, he fits every description,” she explained.

Brandiss Pearson, a nurse and mother, spoke up as a parent of a black teenager. She said she is concerned daily about her son’s safety. “Having a 16-year-old black son who is 6-foot-2, 260 pounds, he fits every description,” she explained.

Her greatest fear: Her son would be mistakenly identified as a suspect and targeted because of a snap judgment by an officer. As a mother of two teen boys and wife to a corrections officer, she said she has a broad perspective, but still can’t shake her fear. One reason she participated was to learn what her son should do if approached by an officer. “If he’s ever stopped, what do I tell him to do?” she asked.

McGork said that officers are taught that race cannot be part of the equation, explaining in legal terms that race and gender are not “articulable facts.”

“So it would always be improper to ID a suspect solely on race,” he said. Officers must use a more accurate description such as tattoos, scars, specific clothing — not just a black male, tall and heavy-set. Rusin later clarified that courts have determined race and gender are not reasonable factors, but descriptions like size, height and weight are.

When describing what police refer to as “investigatory stops” — which many equate with the now unconstitutional New York City stop-and-frisk tactic — McGork said the purpose is to preserve safety and minimize crime. McGork explained that the more information or suspicion an officer has, the more intrusive an officer can be (People v. DeBour).

“But we’re not often great communicators,” he conceded of police officers. “I think many times we could do a better job at explaining why and what we are doing.”

But if there is immediate concern for public safety, some details could be withheld by police and an officer’s actions could become more forceful. Clifford Ryans, who is with O.G.s Against Violence and a member of the city’s Citizen Review Board, told the group that once he was told he “fit the description” of a robber and was pulled over by an officer.

“Actions of officers would depend on who made the tip and how detailed the description was — is there reasonable suspicion?” McGork said. “The officer has to make that determination.”

One attendee suggested that if students wore school uniforms, officers could recognize them as a non-threat. Another muttered that the logical deduction is that the teen would be stopped because of an officer’s unconscious bias.

“This is something we teach,” McGork said in reference to stereotyping. “It is improper to base on race, because race can’t be part of the equation.”

McGork’s closing thought: “As an officer out on patrol, I know that 139 cops were killed last year. I don’t want to be number 140.”

The compelling question posed by the mother, Pearson, left a division in the room. Her plea for something she could instruct her son to do, something to possibly spare his life if he were stopped by an officer, fell flat as the sergeant tried to convey how a cop approaches the same situation with an equal level of fear.

The compelling question posed by the mother, Pearson, left a division in the room. Her plea for something she could instruct her son to do, something to possibly spare his life if he were stopped by an officer, fell flat as the sergeant tried to convey how a cop approaches the same situation with an equal level of fear.

One citizen participant, pastor Antwan Chavis, concluded: “But when approached by a police officer, the kid is thinking: ‘This may be my last day alive.’”

The familiar scenario was not addressed again until the second night, when Pearson posed the same question to Rusin.

Rusin said he impresses upon new recruits that they are acting as extensions of the law and must be apolitical and remove all prejudices.

“You (police) have to go into a citizen encounter knowing that someone may have this initial assumption or fear of you,” Rusin said. “So our demeanor should always be professional; we stress this in our training.”

Later, Rusin was asked about dealing with people with mental health issues and who have conditions such as autism. He said training is the key, again, and commented that he has two young nephews with autism who hate to be touched. He described much of policing as observing and reading cues. SPD recruits do a week of training on mental health, he said, and the issue overlaps into other portions of instruction as well. In total, training that is focused on mental health issues runs close to 80 hours, he said.

Additionally, Rusin said the state requires seven hours of use-of-force training for new recruits. However, because SPD sees this as vital, he says the department does closer to 70 hours of training. New recruits are also required to take implicit bias tests to measure attitudes, stereotypes and other hidden biases that can influence perception, judgment and action.

Chavis posed one more question, asking Rusin if he personally thought police brutality is happening locally.

Instead of answering, Rusin posed the question back to guests: “What might I base my answer on?”

Someone answered: “Data.”

Rusin responded: “But data doesn’t always meet perception.”

As an example, he discussed how many people use Facebook as a news source and noted that video shot on cellphones often only shows a narrow view of an incident.

So what gives an officer the right to use force?

In New York state, it is Article 35. This statute outlines the rules and regulations referring to the use of physical force and deadly physical force based on what an officer believes necessary.

To teach recruits what is deemed necessary, Rusin says, it starts with review of laws and court cases, plus scenario trainings.

In the final two days of the civilian police academy, participants could volunteer to try different practical exercises — fighting off someone with a knife, responding to disorderly calls with unknown outcomes, even working in a team in an active-shooter scenario where participants maneuvered through a portion of the jail.

Critical decision-making was required to determine if the citizen-now-cop needed to simply calm someone down with talk, hold someone off until backup could arrive or draw a gun, using deadly force. For some, it was shocking to see the quick reaction time required to complete the simulation correctly.

Critical decision-making was required to determine if the citizen-now-cop needed to simply calm someone down with talk, hold someone off until backup could arrive or draw a gun, using deadly force. For some, it was shocking to see the quick reaction time required to complete the simulation correctly.

Officers explained that they might have several minutes to hold off an attacker before backup could arrive. Most simulations at the academy lasted only 60 seconds, showing the physical exhaustion that can set in after a short time.

Participants were also reminded to observe their surroundings, never knowing if someone might have a cellphone pointed at them or if an additional attacker could be lurking out of sight.

One officer said: “There’s many people angry at the uniform right now.”

The new norm, Rusin said, is training, including understanding different cultures. He noted that Syracuse has many refugees.

“Train, train, train,” he said. “Train on how to interact and work with cultural differences. Training is the fluid movement of the police department.”

— Article by Ashley Kang, The Stand director

The Stand Syracuse

The Stand Syracuse