Gwendolyn Maturo-Grasso teaches students lessons for school and for life

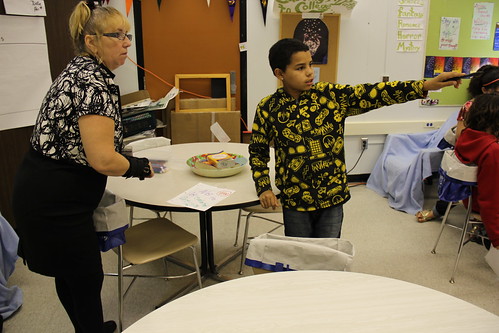

One recent day at 7 a.m., a classroom inside Lincoln Middle School library is already crowded with students from the STEM club. Gwendolyn Maturo-Grasso, wearing a black brace that resembles a fingerless glove, asks the students to think about how to distribute weight to make a bridge stronger.

Maturo-Grasso, 51, has been teaching English and science at Lincoln Middle School since 1986. She is the founder of the school’s STEM club. About half the club members are from the South Side of Syracuse, she said about STEM, which stands for Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics.

In her role as the club’s mentor, Maturo-Grasso cultivates passions for science and technology in a school where an estimated 80 to 90 percent of the students come from families that are receiving public assistance, according to the New York State School Report Card in 2010-2011.

“She has a very strong passion for students, making sure that they are able to get ahead, to function with their highest ability,” said Suzanne Detore, a high school science teacher who has taught many of Maturo-Grasso’s former students. Detore helps Maturo-Grasso to organize STEM club activities.

Trained as an English teacher, Maturo-Grasso attended a program in 1999 that she says broadened her vision. “It taught me the power of using technology,” Maturo-Grasso said of the Southeastern Consortium for Minorities in Engineering program.

Maturo-Grasso started creating science activities and lectures for students. She connected schools with technology companies and founded STEM at Lincoln Middle School in 1999. In recent years, the STEM club has competed in the Syracuse Soap Box Derby, Salt City Technical Robotics Competition, and Build ’em and Bust ’em bridge building competition.

Maturo-Grasso started creating science activities and lectures for students. She connected schools with technology companies and founded STEM at Lincoln Middle School in 1999. In recent years, the STEM club has competed in the Syracuse Soap Box Derby, Salt City Technical Robotics Competition, and Build ’em and Bust ’em bridge building competition.

Now Maturo-Grasso is pursuing a doctorate degree in instructional design, development and evaluation at Syracuse University. She says that the model she wants to set for her students is constant learning.

Passion and knowledge, however, are not enough in a time when many schools, including Lincoln Middle, are besieged by financial difficulties. Detore recalled one such struggle in 2011 when Maturo-Grasso tried to organize a VEX Robotics Competition. She had to go through every logistical detail, including where to seek funding and where to hold the event. Much of the preparations meant spending several hundred dollars out of pocket and sacrificing time outside of her typical work hours.

“She will do anything, make any sacrifices for any of those kids. She has gone beyond teaching,” said retired teacher Eduardo Rodriguez, who has worked with Maturo-Grasso and the STEM club for almost a decade. “The way she nurtures them, every student became a family.”

She has been told many times by her family and colleagues that it is impossible to save everyone, but she is unable to accept the possible consequences of inaction.

Several weeks ago, a father lost his temper in the teachers’ offices, bursting out abusive words and throwing his son’s stuff everywhere. The first thing that came to Maturo-Grasso’s mind was “the boy can’t go home with a father like this.” She contacted child protective services and ensured someone from the extended family could be there for the boy after school. Later, the school discovered the father had psychotic disorders and was unable to control his emotions.

“What if I said I couldn’t save them all?” Maturo-Grasso asked rhetorically. “I never had that attitude, never.”

Maturo-Grasso believes the widely accepted “rigor-relevance-relationship” education theory, which encourages repeating good behaviors first and then building connections, should be reversed.

A colleague explains Maturo-Grasso’s teaching philosophy. Establishing mutual respect and relationships, according to Heather Jenkins, an English teacher in the school, is always Maturo-Grasso’s priority.

“She taught me how to create a strong bond between the students,” Jenkins said. “First you have to create a relationship and then you can become a teacher.”

In her English class, Maturo-Grasso chooses books that students can relate to, such as Gary Paulsen’s “Hatchet,” a story about how a 13-year-old boy from a broken family survived in the wilderness after a plane crash.

“Those kids are living in rough neighborhoods, and they are all about survival. They don’t think about the future,” she said. “I am not just teaching them science and literature, I am trying to teach them to be responsible, professional, to be the best they can be.”

Maturo-Grasso finds a strong personal connection with her students. She grew up in subsidized housing, sharing a small bedroom with three sisters. But she had an extraordinarily strong mother who told her never to be ruptured by any ills or difficulties, to always “put on a smile” for a new day. She found the advice helpful, especially when she later became a single mother with endless bills to pay. She said no matter how frustrated she felt, giving up was never an option. When many of her students became the first in their families to choose a college path, this belief was deepened.

People wonder why Maturo-Grasso always wears a black brace on her arm.

Seven years ago, while trying to stop a fight in the hall, she smashed her hand on a locker door. The tendon and ligaments were seriously injured, making it hard to even lift her thumb. After three surgeries, she still cannot open a doorknob with her right hand. And now she has to wear that protective brace every day.

But there are too many things crammed in her head this early morning to think about her physical pain. She talked about buying a weekly pillbox for a girl who always forgot to take her medicine; she spoke to a boy with a troubled mother and a father in jail about getting back to the classroom; she tried to persuade an improperly dressed girl to change her mini shorts. And when the bell rang and the class started, she smiled — like her mother taught her — just as she has each day in this school for the past 26 years.

— Article and photos by Maya Gao Qian a graduate student at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications

The Stand Syracuse

The Stand Syracuse