During third speaker series, keynote encourage Syracuse to have a wider vision

William Shakespeare, Winston Churchill and Albert Einstein were present in spirit in the Onondaga County Civic Center on Sept. 24.

Peter Park used phrases attributed or misattributed (in Einstein’s case) to these historical figures and others to buttress his arguments during his lecture titled “Remove a Highway, Improve a City.”

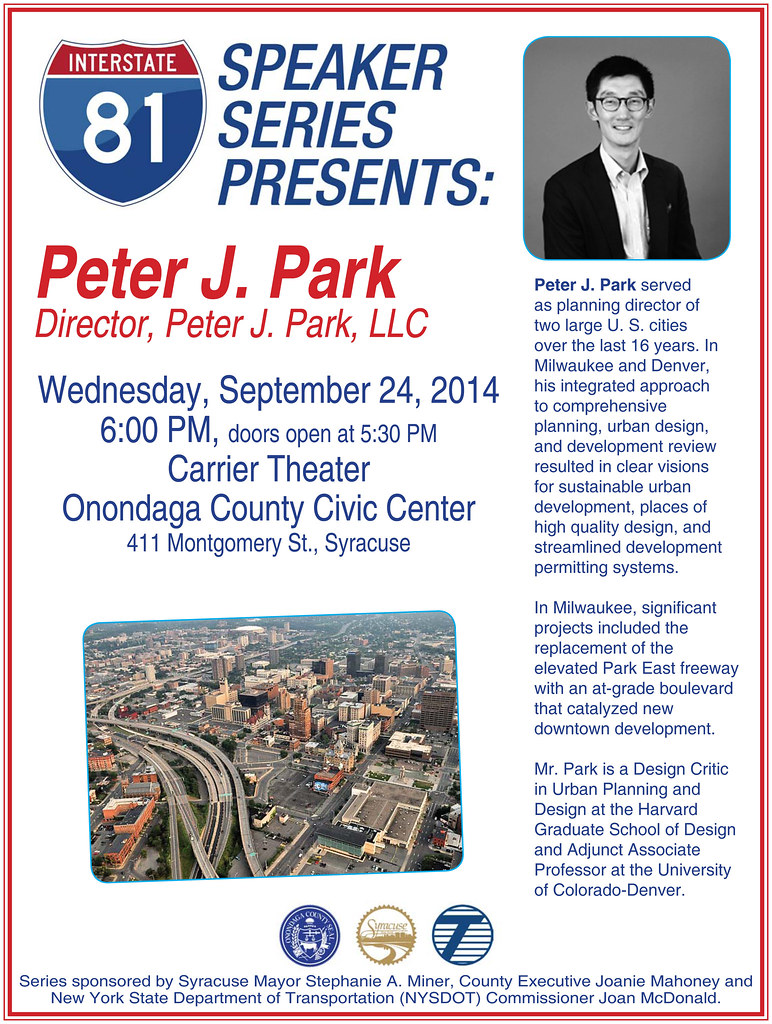

Park, a visiting critic in the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University, was featured in the third installment of the Interstate 81 Speaker Series, jointly organized by the City of Syracuse, Onondaga County and the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT).

Park, who was praised by Mayor Stephanie Miner for his “innovative planning and creative practice,” addressed the question that NYSDOT is posing to Onondaga Country residents: “What would we do about the I-81 highway?” He said that the Draft Scoping Report (DSR) and the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), carried out by the NYSDOT as required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), by framing the discussion around this question, provides too short a set of options to the public. Instead, he proposed asking a larger question: “What would the city aspire to?”

Park advocated a holistic approach, whose object of study is the system of urban metabolism, and opposed this to a reductive and technocratic approach, which reduces the object of study only to the I-81 highway. In other words, he favored looking at the forest and not just at a tree.

“The real questions are not technical,” he said, illustrating these questions as referring to vehicle miles traveled, turns, clearing time, signal phase, routing options, etc. “Rather, the real questions are questions of political will from the community.”

Park suggested that now there is encouragement for people to serve cars in lieu of cars to serve people. He took a historical perspective to argue how this situation came to be. He said that a contributing factor to its genesis was a propaganda campaign orchestrated by car companies in the mid-’50s to try to influence the Eisenhower administration in shaping the characteristics of the Interstate Highway System, whose construction was approved by the Federal Aid Highway of 1956. To this effect, Park added, the General Motors Corp. and the Ford Motor Co. released promotional films titled “Give Yourself the Green Light” in 1954 and “Freedom of the American Road” in 1955, respectively, which equated driving an automobile with freedom.

“In the mid-’50s in America it became almost an imperative, a civic responsibility, to drive cars. Driving them was identified by their manufacturers as freedom of choice, freedom to come and go as we please,” Park said. “The aim of the campaign was to convince folks that it was their patriotic duty to dream big enough as a nation on wheels because we were running out of roads.”

Park contraposed this vision to those of urban planners at the time, Lewis Mumford and Jane Jacobs, who, he said, understood the city grid as fine-grain network of blocks that shouldn’t be disrupted by an improved highway. Park suggested that this debate was not new in the United States. In the ’20s, architect Le Corbusier advocated investing taxpayer money to accommodate more automobiles, Park went on to say, contrasting this view with that of Werner Hegemann, a critic of this architect’s plans.

Park said that President Dwight Eisenhower was against having highways cut through cities as part of the Interstate Highway System but local authorities lobbied for this option.

Park added that highways going through cities have a design flaw that induces traffic and produces moments of congestion. “Motorists in a highway have to drive further to get off it and then come back in the city streets,” he said.

He recounted his experiences as a former planning director for the cities of Milwaukee and Denver to make the case that, given a choice, most people wouldn’t want an elevated highway in their neighborhood. He bolstered his case by citing the reports “The Life and Death of Urban Highways” (2012), “Falling Apart and Falling Behind” (2012), “Rethinking Highways in American Cities” (2013), and “Freeways without Futures” (2014), in the preparation of some of which he participated.

Julius Lawrence, a South Side community member for 20-odd years, and Barry Lentz with the Urban Jobs Task Force, raised similar questions, about the impact of taking down elevated highways on the job situation of city residents. Park replied, “There would an economic boost due to the temporary hiring of local workforce, but not long term.”

Tim Rudd, who identified himself as a city resident, expressed concern that the NYSDOT’s view does not take “99 data points relevant to urban vibrancy into account in the design.” Park seconded Rudd’s notion and suggested that a better method is to transcend NYSDOT’s. “We need to see the the investment potential of the area cleared of the highway, not only traffic performance,” Park said. “DOT’s charge is pretty narrow: to optimize travel. We have to go out of the scope and boundary of DOT’s study.”

Two architects of the advocacy organization ReThink81, Andrew Schuster and Bob Haley, made inquiries related to an “urban/suburban bridge” in the I-81 debate, which, they said, is pitting “the city against towns and villages.” Park responded: “This conversation shouldn’t be an either/or proposition. We need to broaden the conversation, which is now led and dominated by the roadway design, and look at mass rapid transit. Also, at people and their potential for contribution.”

He concluded his presentation by quoting words in the play “Coriolanus” by Shakespeare,”What is the city but the people?”

— Article by Miguel Balbuena, The Stand community correspondent

The Stand Syracuse

The Stand Syracuse