Sentry program works to protect students throughout district

As the first lunch period at Clary Middle School approached, Aaron Wilson rose in preparation. Lunchtime is one of the biggest responsibilities for Wilson, the security officer in the building. He presides over two cafeterias of more than 50 students each.

On this particular day, the school announced that the three lunch periods would be “silent lunches” — talking kept to a minimum.

“I’d like to see this myself,” Wilson said, questioning the students’ willingness to be quiet.

The bell rang, signaling the end of the previous period. “The boys are coming now, and the girls will be coming in four minutes,” he said, referring to the two cafeterias, which are separated by gender. As students filed in, many greeted Wilson by name, and some gave him high fives.

After the students were seated, Wilson began his usual supervision by circling between the two cafeterias. “I walk though and keep an eye out for little signs that something might be escalating.”

Before the students began eating, teachers addressed the room. In the girls’ cafeteria, two students continued to talk while announcements were made. Wilson and other faculty members warned the girls multiple times. Finally, he decided he’s seen enough, and the students were asked to leave the cafeteria, doing so in disbelief.

“I didn’t even do anything,” one of the girls said.

“Me neither,” replied the other. “I’m telling my mom.”

Other than this minor interruption, though, the rest of the period continued without any problems. “It’s funny, this is actually really quiet today,” Wilson observed. “Lunch usually gets crazy. It’s their time to let loose in between classes.”

Other than this minor interruption, though, the rest of the period continued without any problems. “It’s funny, this is actually really quiet today,” Wilson observed. “Lunch usually gets crazy. It’s their time to let loose in between classes.”

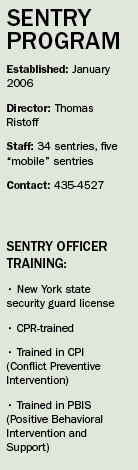

The sentry program, which the Syracuse City School District implemented in 2006, provides schools with security officers like Wilson trained to deal with any disruptions within the building.

Thomas Ristoff, district director of safety and security, describes the program as a way to “build a relationship with students so that when something does happen, we can control the situation with a minimal amount of staff and without being intrusive.”

Sentries like Wilson try to be aware of the personal lives of students. “There’s this whole web of community that comes into the school, and the school extends into the community,” Ristoff said, “so it’s important to know what’s going on, know your students, and be able to foresee what could happen.”

Mike Henesey, district communications coordinator, said Wilson’s constant presence and observation helps cue him to any possible incidents. “If you’re in the hallways you’ll know just from being out and knowing the kids, what’s happening throughout the course of the day and if there’s potential for an argument,” he said.

That is not always the case, especially when incidents occur outside of school. “Unfortunately in today’s society, a lot of students come to school with issues that are beyond their control,” Ristoff said.

Staff members like Wilson are better served when they know about such issues. He recalls a student whose relative in New York City was the victim of a shooting.

“His whole week was just bad,” Wilson said. “He ended up leaving halfway through the week, going down to New York City, and he didn’t come back for another week after that.”

“We call it ‘leakage,’” Ristoff added. “There’s always a precursor to an incident.”

“We call it ‘leakage,’” Ristoff added. “There’s always a precursor to an incident.”

At its inception, the program maintained 20 officers, but it now employs 34 sentries throughout the district. In addition, five mobile sentries are split into geographic sections, helping out at various schools as needed. All sentries are licensed New York state security guards, trained to read indicators of potential confrontations, to defuse them with words rather than force, and to safely restrain a student if necessary as a last resort.

Despite the increased staff over time, Ristoff still worries about limited resources. “For the small amount of personnel I have, they’re busy every day, and they’ll attest to that,” he said.

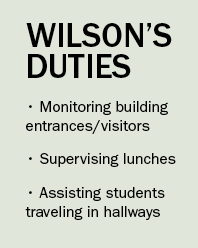

Between supervising lunches, escorting students around the school, and monitoring visitors entering a building with 400 students, Wilson often finds himself running from one spot to another.

“I’m the security officer, I’m the hall monitor, I have to be all over the school at once,” he says.

Sometimes, though, he can’t be everywhere. During another lunch a few weeks ago, Wilson says he walked in on one student hitting another.

“I was walking through the girls’ cafeteria into the boys’,” he said. “I turned around to start walking back in and, sure enough, a girl got up and smacked another girl.” Wilson quickly separated the two students.

Although Wilson takes care of events like these swiftly, he says the key is not just damage control but prevention. “That’s the type of thing we’re trying to look for. We’re trying to stop that whole situation from happening in the first place.”

The Stand

The Stand